We may earn money or products from the companies mentioned in this post. This means if you click on the link and purchase the item, I will receive a small commission at no extra cost to you ... you're just helping re-supply our family's travel fund.

For a long time, travelers assumed beloved places would simply be there when time and money finally lined up. That quiet promise has been breaking. Wildfires, aging pipes, fragile wildlife, and social media overload have pushed famous trails, beaches, caves, and lodges behind locked gates or into strict permit systems. Some closures are temporary, some permanent, and many float in an uneasy “until further notice.” What emerges is a map where the most beautiful corners now come with fine print, limited access, and a nagging sense of running out of time.

Haiku Stairs, Oahu, Hawaii

For decades, the Haiku Stairs felt like a shared secret that was not really secret at all. Locals and visitors climbed a rusting Navy staircase before dawn, ignoring no-trespassing signs for a sunrise above the clouds. Safety risks, rescue costs, and neighborhood tensions finally tipped the scale. The city voted not just to close the route but to remove the staircase altogether and seal off key access points. What once lived as an off-the-books badge of courage is shifting into memory, with only old photos mapping the climb.

Havasu Falls, Havasupai Reservation, Arizona

Havasu Falls used to symbolize a lucky break in the campground lottery and a hot, dusty hike rewarded by turquoise pools. Floods, overcrowding, and the pandemic showed just how fragile that setting really is. The Havasupai Tribe has closed and reopened access on its own timeline, cancelled full seasons, and raised prices to reflect the true cost of hosting outsiders. Permits sell out quickly and remain nonrefundable, lodging remains tightly controlled, and last-minute detours are nearly impossible. The canyon still glows, but it does so under rules written to protect tribal land first.

Angels Landing, Zion National Park, Utah

Angels Landing has always been about fear and perspective, a narrow spine of rock lined with chains and sheer drops. As crowds grew, the route turned from thrilling to dangerous, with hikers queuing on exposed ledges and rescue calls piling up. Zion responded with a permit lottery to ration access. Would-be hikers now apply well in advance or try a last-minute drawing, pay a fee, and carry proof of permission. The trail still runs along the same stone, but the chance to feel that exposure has become a scheduled event, not a spontaneous dare.

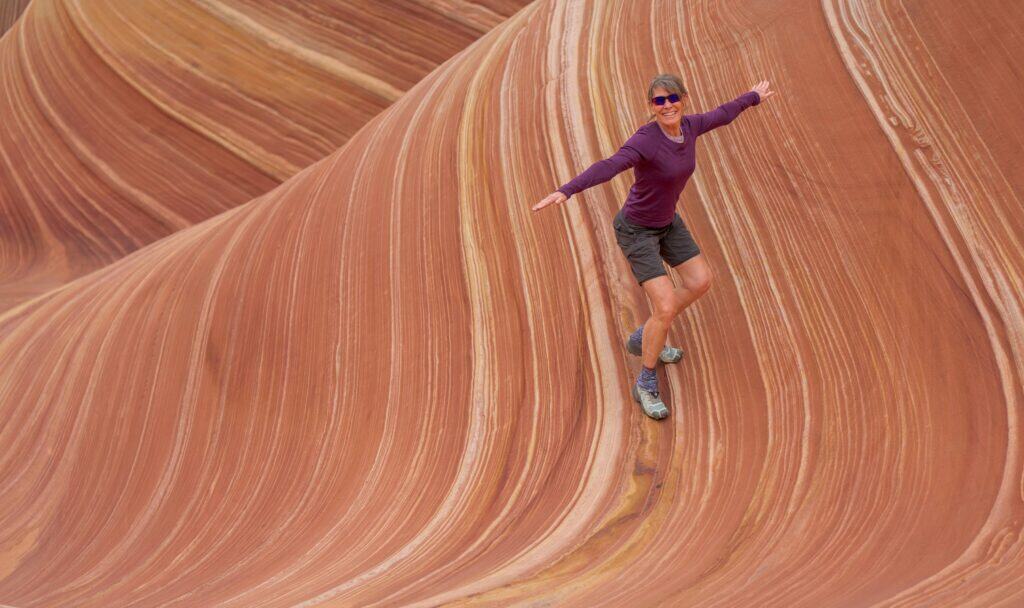

The Wave, Coyote Buttes North, Arizona–Utah

The Wave looks almost unreal in photos, which is exactly the problem. Images bounced across social media far faster than the rock could absorb human footsteps. Land managers moved early to protect the fragile sandstone, capping daily visitor numbers and enforcing a strict permit system. Most permits are awarded months ahead, with a smaller pool held for a day-before lottery that requires being physically nearby. Many hopeful hikers never touch the rock itself. For them, the Wave exists as an inbox full of “not selected” messages and a reminder that some beauty must stay scarce.

Kalalau Trail And Nāpali Coast, Kauai, Hawaii

The Nāpali Coast once felt wild but loosely regulated, with hikers and campers pushing into valleys that could not absorb endless use. Heavy rain, landslides, and years of crowding forced the state to reset expectations. Access to Haena State Park now runs through timed reservations, while overnight permits for the Kalalau Trail are limited and tightly enforced. Drivers without park bookings are turned away at the gate, no matter how far they have come. The coast has not changed, but the human presence feels quieter and more deliberate, with fewer stories of chaotic, overflowing camps.

Antelope Canyon, Navajo Nation, Arizona

Antelope Canyon’s light beams now appear in screensavers, phone wallpapers, and travel ads, but the real slot has never been able to hold that level of attention. After safety incidents and pressure on the land, the Navajo Nation shifted to a guide-only model. Visitors must book with authorized operators, follow tight schedules, and move in controlled groups through the narrow passage. Independent wandering is no longer an option. The canyon remains visually overwhelming, yet the experience now includes a clear reminder that it is also a cultural and spiritual site, not just a backdrop for photos.

Grand Canyon Lodging And North Rim Losses, Arizona

For many families, the Grand Canyon is not just a view, it is a hotel room perched on the edge and a sunrise seen in slippers. That part of the experience has taken repeated hits. Aging water infrastructure on the South Rim has forced partial closures and emergency repairs, limiting how many lodge rooms can operate at once. On the North Rim, fire recently destroyed the historic Grand Canyon Lodge, erasing a centerpiece of that quieter side. Day visits and rim overlooks remain open, but the classic “stay on the edge” dream now depends on forces no one can fully predict.

Chisos Basin, Big Bend National Park, Texas

Big Bend’s Chisos Basin has long been the park’s natural living room, a high bowl where trails, lodge, and campground all meet under jagged peaks. Structural issues, failing utilities, and the age of the lodge finally caught up with that setup. The National Park Service closed the entire Basin area for a multi-year rebuild, shutting down the lodge, restaurant, visitor center, and nearby campgrounds at once. Scenic drives and desert trails elsewhere in the park remain open, but first-time visitors often discover that the easiest, most iconic base camp has gone offline for now.

Glass Bottle Beach, Dead Horse Bay, New York

Glass Bottle Beach at Dead Horse Bay sat at the edge of New York City history, a place where waves unearthed old bottles, toys, and industrial scraps from a buried landfill. Photographers and curious walkers treated it as a strange, shimmering archive. Tests later raised concerns about contamination, and officials closed the southern portion of the bay for cleanup and safety work. The beach now sits behind fencing and warning signs. The same tide that once revealed relics now rolls in largely unseen, while memories of found objects turn into cautionary tales about long-buried waste.

China Camp And Cluster Point Beaches, Channel Islands, California

China Camp and Cluster Point on the Channel Islands never hosted the same crowds as mainland beaches, but even light traffic can damage sensitive dunes and nesting grounds. Managers closed these sections to public access, letting the sand, plants, and birds reclaim space previously crisscrossed by footprints. Visitors still reach the islands and enjoy other beaches and trails, yet whole stretches remain deliberately empty. The closures can feel abrupt to those reading old guidebooks. On the ground, the absence of umbrellas and coolers is exactly the quiet these shorelines needed.

Sandy Point National Wildlife Refuge, St. Croix, U.S. Virgin Islands

Sandy Point looks like a classic Caribbean postcard, but its schedule runs on turtle time. The refuge is one of the most important leatherback nesting sites in the region. To keep those nests safe, the beach closes completely during the peak season and opens only in tight windows the rest of the year. Rules ban pets, bright lights, and anything that might disturb the sand. Visitors who happen to arrive on a closed day meet locked gates and explanatory signs. The trade is clear: fewer human footprints now to ensure hatchlings still emerge in future summers.

Seal Beach National Wildlife Refuge, California

Seal Beach sits in a heavily developed corner of Southern California, boxed in by neighborhoods, roads, and a naval weapons station. Inside the refuge boundary, the priorities flip. Access is restricted to special tours and approved programs designed around sensitive species. There are no casual boardwalks or drop-in viewpoints. For most travelers, the place exists mainly as a name glimpsed on a sign along the highway. Its real work happens out of sight, in quiet tidal channels where threatened birds and turtles move without the constant disturbance of beach crowds.

Wolf Island National Wildlife Refuge, Georgia

Wolf Island lies off the Georgia coast as a kind of deliberate absence in local tourism brochures. The refuge keeps its beach, marsh, and uplands closed to public entry in order to protect nesting shorebirds and other wildlife that cannot share space easily with people and their dogs. Boats may pass offshore, and nearby islands offer plenty of sand for visitors, but Wolf Island itself is meant to be experienced at a distance. Its value rests in being left alone, a rare patch of coastline where the only regular footprints belong to birds.

Guadalupe-Nipomo Dunes National Wildlife Refuge, California

The Guadalupe-Nipomo Dunes look built for adventure, with sweeping sand hills and a long Pacific horizon. Yet many sections are off-limits by design. Wetlands and the panhandle area remain closed to public entry, marked by signs that ask people to stop at invisible boundaries. The aim is to protect rare plants and nesting birds that rely on undisturbed sand. Nearby access points and neighboring beaches still welcome visitors, but the refuge itself insists that not every dune can hold tire tracks and picnic blankets. It is a reminder that some scenery has a different job to do.

Nutty Putty Cave, Utah

Nutty Putty Cave once attracted scout groups, college students, and curious locals eager to squeeze through tight passages in the Utah clay. A fatal entrapment in 2009 forced a reckoning about what level of risk could ever be acceptable in that maze. Authorities sealed the only entrance and later filled parts of the cave, effectively burying it for good. The surface shows just a plaque and a hillside. The cave now survives mainly in memories, rescue reports, and a film that tried to capture its claustrophobic pull. Adventure in that particular hole is over by design.