We may earn money or products from the companies mentioned in this post. This means if you click on the link and purchase the item, I will receive a small commission at no extra cost to you ... you're just helping re-supply our family's travel fund.

A story once told as a single march across a frozen bridge is being rewritten in layers of mud, stone, and ancient DNA. Researchers now argue that the earliest movement into the Americas likely hugged the Pacific rim, using watercraft to travel between islands, kelp forests, and ice-free pockets long before an inland corridor could sustain people. Footprints, coastal deglaciation dates, and early sites far south point to a journey that mixed paddling with short portages, guided by food-rich shorelines rather than one long trek over land.

Footprints From The Last Ice Age

At White Sands in New Mexico, footprints pressed into the mud of ancient Lake Otero have been dated to roughly 21,000 to 23,000 years ago, and newer lab work has reinforced that range. The prints include many small tracks consistent with children, implying family groups moving across a wet shoreline shared with mammoths, camels, and giant ground sloths. Because the site records movement rather than settlement, it does not reveal boats directly yet it forces any entry scenario to explain how people reached the interior while ice still locked much of the north, and why the trail of camps is so hard to find today.

The Ice-Free Corridor Opened Too Late

For decades, the classic narrative depended on the Ice-Free Corridor between the Laurentide and Cordilleran ice sheets, a passage imagined as a walkable gateway into the continent. Cosmogenic exposure dating published in PNAS places the corridor’s full opening at about 13.8 ± 0.5 thousand years ago, and other work argues that even after ice retreated, the route was dominated by meltwater, floods, and sparse resources before it became biologically usable. With accepted sites appearing earlier, the corridor now looks like a later highway for movement and exchange, while the first entry needed another path ahead.

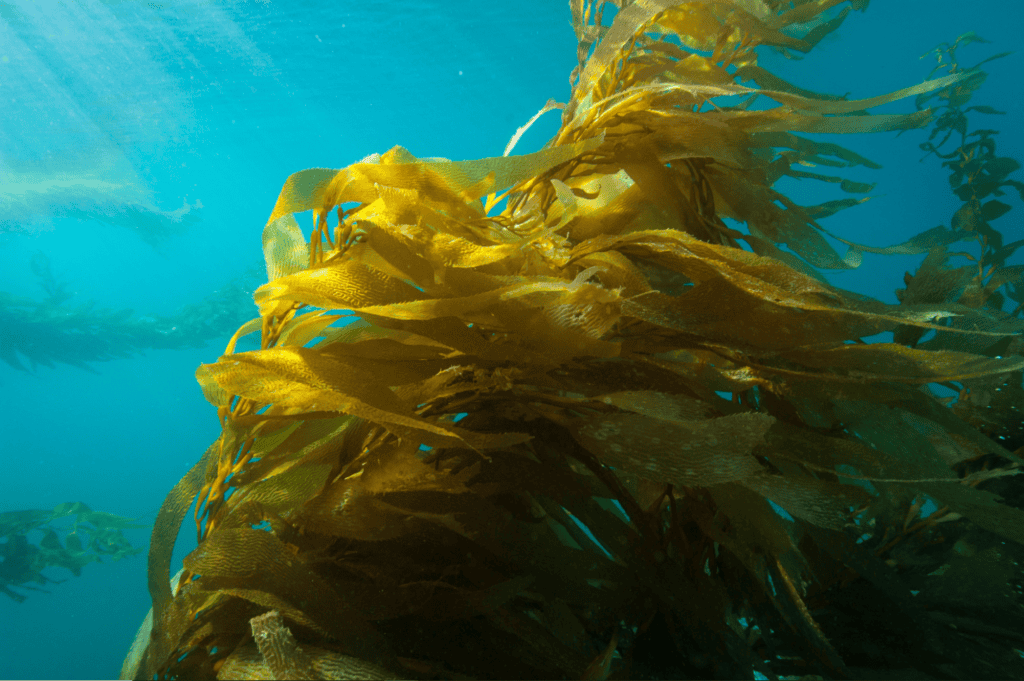

Kelp Forests Offered A Natural Pantry

The kelp highway hypothesis reframes the Pacific edge as a food system rather than a barrier, with nearshore kelp forests supporting shellfish, fish, seabirds, and marine mammals over long distances. Because those resources repeat from cove to cove, coastal travelers could move without gambling everything on rare big-game kills, pausing at estuaries for fresh water and protected landings. In that light, early boats are not a romantic add-on; they are a sensible tool for following a predictable pantry when inland ice, lakes, and floods made deep travel dangerous, and for bypassing headlands and fjords safely.

Early Sites Appear Far From The Corridor

Accepted early sites appear across the Americas in times and places that strain the idea of a single inland gateway. Monte Verde II in southern Chile is widely dated to about 14,500 years ago and preserves plant remains that include seaweed, while Page-Ladson in Florida documents people butchering or scavenging a mastodon about 14,550 years ago, showing a rapid reach to far coasts and lowlands across continents. When evidence shows people living both deep in South America and on the Gulf Coast so early, shoreline travel followed by river travel fits better than a slow wait for an interior corridor to green up.

Cooper’s Ferry Suggests A Pacific Entry

At Cooper’s Ferry on Idaho’s Salmon River, a well-dated artifact assemblage pushes human presence in the interior Northwest to around 16,000 years ago. The authors argue that such timing is difficult to square with an inland corridor that was still blocked or ecologically thin, and they note tool forms that resemble Northeast Asian traditions from the same broad period. The river setting also matters: a coastal arrival naturally turns into upstream travel, with water serving as the first road, and stone points and camps appearing along bends where food and shelter concentrate, long before Clovis-style points.

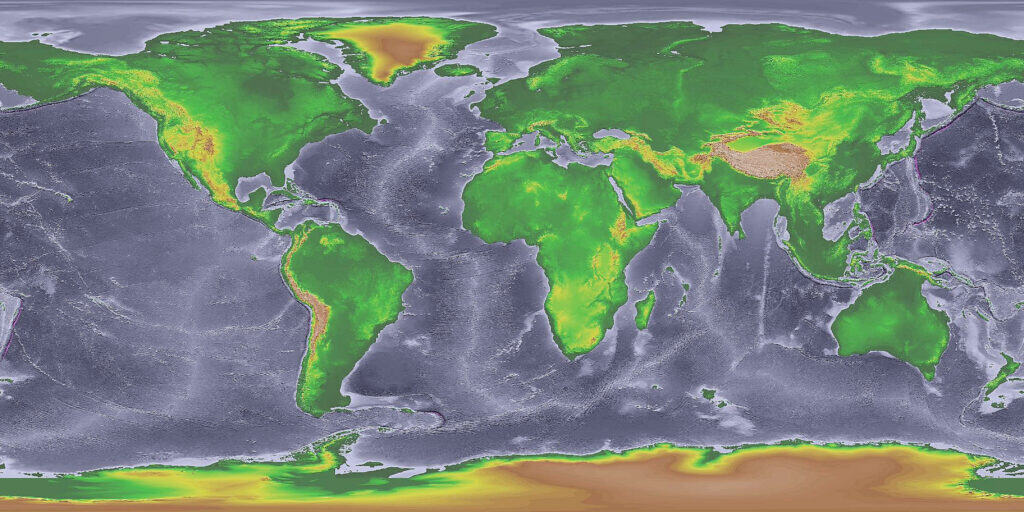

Sea Level Rise Hid The First Camps

Coastal migration sounds hard to prove because the best evidence may now be underwater. After the last glacial maximum, rising seas and complex local uplift reshaped the Pacific margin, submerging ancient shorelines where early camps, boat landings, and shell middens would have been easiest to place. Sea-level studies along Canada’s Pacific coast show how dramatically relative sea level could swing by hundreds of meters, meaning the archaeological map has been physically erased and rewritten, leaving gaps that look like silence but may be drowned data and forcing researchers to chase it with sonar and coring.

Ocean And Ice Set The Rules Of Travel

A coastal route was never a single open highway; it was a moving target shaped by sea ice, currents, storms and the changing edge of the Cordilleran Ice Sheet. A 2023 PNAS analysis emphasizes that feasibility depended on oceanographic and climatic windows and on the strength of coastal currents, too, with some stretches blocked by ice or dangerous drift while other corridors briefly opened up along protected passages. That shifting geography supports a mixed strategy: boats for the long reaches, cautious timing for crossings, and short overland carries around headlands when the shoreline turned into a wall of ice or surf.

Experimental Seafaring Makes Boats Plausible

Direct boats rarely survive for 15,000 years, so researchers test plausibility by showing what people with stone-age tools can do on open water. In 2025, a team paddled a dugout canoe from Taiwan to Japan’s Yonaguni Island across the strong Kuroshio Current, using replicated tools and demonstrating that skilled crews can manage long, exhausting crossings without modern navigation. The voyage is not a Beringia re-enactment, but it chips away at the idea that late Pleistocene people were trapped on land, making a coastal entry into the Americas by watercraft feel technologically ordinary, and done by necessity, not spectacle.