We may earn money or products from the companies mentioned in this post. This means if you click on the link and purchase the item, I will receive a small commission at no extra cost to you ... you're just helping re-supply our family's travel fund.

Mountain lions, also called cougars, live quietly across wide swaths of the American West, moving through canyons, pine forests, deserts, and rimrock mostly unseen. Their presence is not uniform, and it shifts with prey, habitat, and human growth, so state wildlife agencies track sightings, conflicts, and breeding areas. In the East, the story narrows to Florida’s panther stronghold, where recovery remains fragile. These 15 states still hold resident populations or known breeding pockets, often in rough country that looks empty until dusk proves otherwise.

Washington

In Washington, cougars roam the forested spine of the Cascades and the deep green folds of the Olympics, where deer, elk, and brushy cover keep big cats moving along ridgelines, clear-cuts, and river valleys. Encounters tend to flare where trail networks and expanding suburbs press into timber, so the state emphasizes reporting, pet and livestock practices, and quick verification when a sighting travels faster than facts. On the drier east side, cougars still slip through ponderosa draws and basalt canyons, reminding residents that wild country does not end at the county line, even when the nearest coffee shop is minutes away. Most days, too.

Oregon

Oregon’s mountain lions favor the shadowed slopes of the Cascades, the Coast Range, and the broken timber country that links them, following deer through clearings, burns, rain-soaked valleys, and thick re-growth near the snowline. Because the state holds both remote backcountry and busy recreation corridors, sightings can ripple into headlines, with wildlife staff separating rumor from sign, and urging residents to keep pets close and remove food that attracts prey. In the high desert east, cougars still work rimrock and juniper draws above ranchlands, proving the species thrives far beyond postcard forests when water is scarce too. By fall.

California

California holds some of the most varied mountain lion habitat in the country, from chaparral foothills outside Los Angeles and San Diego to the Sierra Nevada’s conifer basins, granite passes, and volcanic plateaus. Because lions are protected as a specially protected mammal in the state, management leans on monitoring, public reporting, and targeted action when a cat lingers near homes, pets, or popular trailheads. Along the coast brushy canyons, wildfire regrowth, and deer corridors can funnel lions close to suburbs, creating a steady tension between wild space and the state’s relentless growth even when the hills look tame at noon in May.

Nevada

Nevada’s mountain lions live in a state built from isolated ranges, where pinyon-juniper slopes rise from sage flats, saltbush basins, and desert playas, and water decides where every animal can linger. Lions follow mule deer through canyon mouths, spring-fed draws, and rocky benches, sometimes shadowing bighorn country, and crossing long distances between “sky islands” that look separate on a map. Because towns and highways pinch those corridors, many conflict stories begin with deer drawn to irrigated yards, then a lion that arrives after dark, tests the edge of a neighborhood, and vanishes before morning as quietly as wind. In winter, too.

Idaho

Idaho’s cougars are woven into big, rugged country, from the Salmon River breaks and central wilderness to the Panhandle’s cedar forests, snowy ridges, and dark north-facing canyons. The cats move on the same seasonal schedule as deer and elk, slipping along game trails, old logging roads, and creek bottoms where cover stays thick, and where tracks can vanish under new snow by noon. In farming valleys, sightings often follow prey that winter near hay fields and irrigated edges, which is why biologists stress that “attractants” usually mean deer, not garbage, and that prevention starts with habitat around the yard. Even on calm moonlit nights.

Montana

Montana’s mountain lions hold the state’s roughest seams, from the Bitterroots and the Cabinets to the Continental Divide’s steep drainages, and into the breaks where prairie gives way to coulees and ponderosa pine. They often travel with edges, using timbered draws and rimrock for cover, and stepping into open country only when light drops and prey begins to move. Because Montana spans ranchland, reservation borders, and vast public forest, management becomes a patchwork of local conditions, with tensions rising where deer and elk winter close to hay stacks, barns, and calving pastures, then pull lions into the same corridors in late winter.

Wyoming

Wyoming’s mountain lions occupy steep, prey-rich country from the Bighorns to the Wind River Range, across the Absarokas, and along the fringes of the Greater Yellowstone ecosystem. They favor broken terrain where cliffs, timber, and sage pockets let them hunt unseen, especially in winter when deer and elk concentrate on south-facing slopes and tracks write stories in snow. Because the state is defined by long distances, open basins, and highway corridors, reports often come from hunters, ranchers, and backcountry crews who learn that one ridge can hold both fresh elk trace and a lion’s quiet shadow before the wind erases it by midday, often.

Utah

Utah’s cougars move between alpine timber, and red-rock canyon country, living in the Wasatch, the Uinta Mountains, and the steep benches that drop toward desert basins. Mule deer migrations shape much of that movement, so lions often surface where winter range sits close to towns, foothill trailheads, and ski access roads, especially after a hard snow that pins prey low. In the southeast, rugged plateaus and side canyons provide cover that feels endless, and management often turns on specific incidents, from livestock losses to repeated neighborhood sightings, rather than broad removal because habitat is vast and sightings are brief at dusk.

Colorado

Harrison Fitts/Unsplash

Colorado’s mountain lions are part of everyday ecology across the Front Range foothills, the Western Slope, and canyon systems that thread from sage mesas up into spruce and aspen. As more neighborhoods press into wildland edges, lions can show up on doorbell cameras or along greenbelts, often following deer that browse ornamental shrubs and finding cover in creek bottoms and open-space patches. The state’s approach balances public safety with coexistence, relying on reports, education, and targeted response when a specific animal repeats risky behavior, rather than treating every track, scrape, or fleeting silhouette as an emergency at dawn.

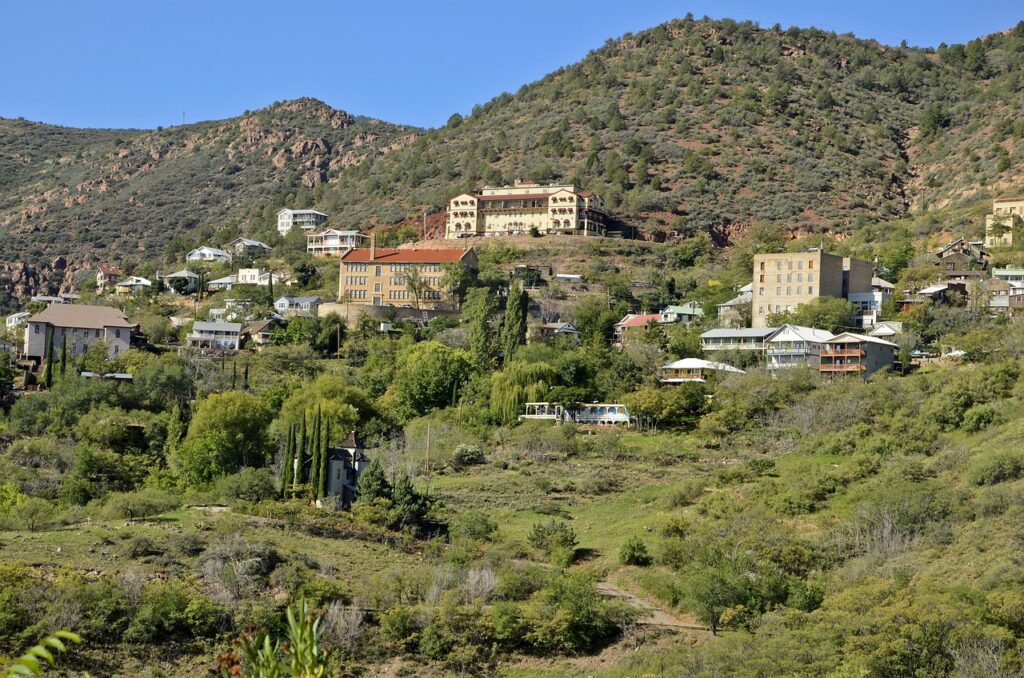

Arizona

Arizona’s mountain lions live where desert meets elevation, using the sky islands of the south, the Mogollon Rim, and pine-clad ranges that rise above saguaro flats and basalt mesas. They follow deer and javelina through rocky washes, oak canyons, and shaded drainages, and can travel long distances between reliable water when heat tightens the landscape before monsoon storms arrive. Sightings often cluster near foothill neighborhoods and trail networks around Tucson, Phoenix, and Flagstaff, where prey adapts to irrigated edges, and a lion can vanish into a single arroyo or boulder field, as quickly as the light changes at sunset after 6 p.m.

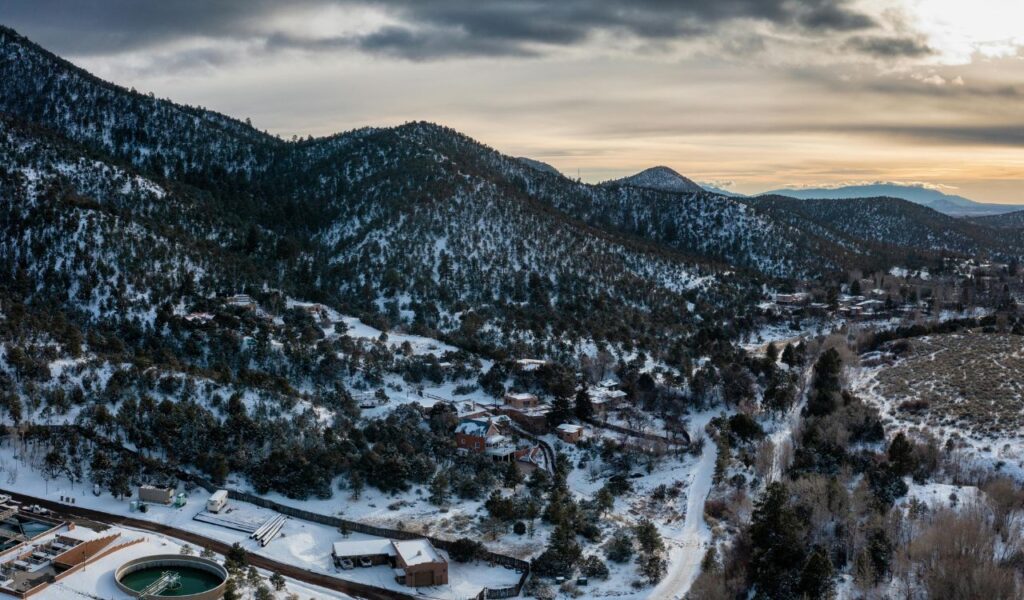

New Mexico

New Mexico’s mountain lions move through a state of sharp contrasts, from the Sangre de Cristo and Jemez high country to the Gila’s canyons, the Sacramento Mountains, and desert ranges that glow at dusk. They track deer across piñon-juniper slopes, lava fields, and cottonwood-lined riparian ribbons that stay green when everything else turns dust, and they can cross huge distances between water and shade. Because public lands dominate large swaths of the map, many signs appear far from towns, yet conflict can flare around ranches where prey concentrates near tanks and corrals, and a lion’s repeat visits turn a quiet season into a watchful one.

Texas

Texas holds mountain lions in its wildest corners, especially the Trans-Pecos and Big Bend country, where rugged ranges and desert basins still offer cover and prey. The cats also appear in brushlands of South Texas and parts of the Hill Country, often moving along arroyos and creek lines that stay hidden from roads, and turning up on ranch cameras before anyone sees a track. Because the state is vast and reports are uneven, perception swings between myth and alarm, yet the pattern is simple: lions follow deer, and they avoid people until development, drought, or a wounded prey animal narrows their options near water on summer nights quietly.

South Dakota

South Dakota’s mountain lions are most closely tied to the Black Hills, where a breeding population has been established and managed as a big game species since the early 2000s. The surrounding plains hold far less consistent cover, so most confirmed activity stays in pine-covered hills, rocky draws, and rugged edges that mimic the West on a smaller scale, with occasional dispersers wandering far beyond. That geography shapes the tone of local life: sightings can feel rare and startling, yet they often reflect predictable movement along deer routes and canyon rims, especially in winter when prey funnels into sheltered terrain near town lines.

Nebraska

Nebraska’s mountain lions returned quietly after being eliminated in the 1800s, and the state now recognizes breeding or documented reproduction in several pockets. The Pine Ridge, the Niobrara River Valley, the Wildcat Hills, and Missouri River bluffs offer cover, deer, and rugged breaks that let a western predator gain a foothold on the Plains, even as farm ground stretches between. Because these populations are smaller and scattered, public sightings can spark strong reactions, yet biologists emphasize careful reporting, verified tracks, and realistic expectations about how rarely a person will actually see one, even when a lion is nearby.

Florida

Florida’s mountain lions survive as the Florida panther, a rare eastern stronghold whose core range sits in the swamps, pinelands, and ranch edges of South Florida. Most breeding females are found south of the Caloosahatchee River, and road networks, development pressure, and habitat fragmentation shape daily survival as much as prey does. Because the population is federally endangered, and closely monitored, the story is less about wide-open wilderness and more about corridors, crossings, and patience, with every confirmed sighting pushing north toward Lake Okeechobee carrying both hope and hard questions about what recovery really requires.