We may earn money or products from the companies mentioned in this post. This means if you click on the link and purchase the item, I will receive a small commission at no extra cost to you ... you're just helping re-supply our family's travel fund.

Skywatchers across the United States are preparing for a rare celestial moment as parts of the country may witness the northern lights on Monday night. Triggered by heightened solar activity, this event could push the aurora borealis far beyond its usual Arctic reach. While auroras are typically confined to high latitudes above 60° north, stronger geomagnetic storms can shift visibility hundreds or even thousands of miles south. This article breaks down exactly what’s happening, where visibility is most likely, and how timing, numbers, and conditions come together to create this unusual opportunity.

1. Solar Activity Behind the Event

The possible aurora display is driven by a coronal mass ejection, or CME, released from the Sun at speeds exceeding 800 kilometers per second. When this plasma cloud reaches Earth, it compresses the magnetosphere and triggers geomagnetic storms. Forecast models suggest storm strength could reach G3 or higher on NOAA’s 5-point scale, strong enough to expand the auroral oval by nearly 1,500 kilometers. Solar wind density may exceed 10 particles per cubic centimeter, a threshold often associated with visible auroras at lower latitudes. These numbers indicate a meaningful, not minor, solar interaction.

2. States With the Highest Viewing Potential

Northern-tier states sit in the best position to see the lights if skies cooperate. Regions near 45° to 50° latitude, including Minnesota, Michigan, Wisconsin, and northern Montana, have the highest probability. Under stronger storm conditions, visibility could extend south toward states near 40° latitude, including New York, Pennsylvania, and parts of the Pacific Northwest. Forecast probability maps suggest a 30–60% chance of auroral visibility in these zones during peak hours. Distance from city lights remains critical, as urban glow can reduce visibility by over 70%.

3. Timing and Peak Viewing Hours

Auroras are most likely when Earth’s magnetic field aligns optimally with incoming solar particles, typically late at night. Forecasts indicate peak activity between 10:00 p.m. and 2:00 a.m. local time, with the strongest geomagnetic fluctuations expected around midnight. Kp index values may climb to 6 or 7, levels that historically correlate with visible auroras well south of Canada. Activity can fluctuate rapidly, sometimes intensifying within 15–30 minutes, so prolonged outdoor viewing increases success. Even brief clear windows during this time could reveal faint arcs or moving bands.

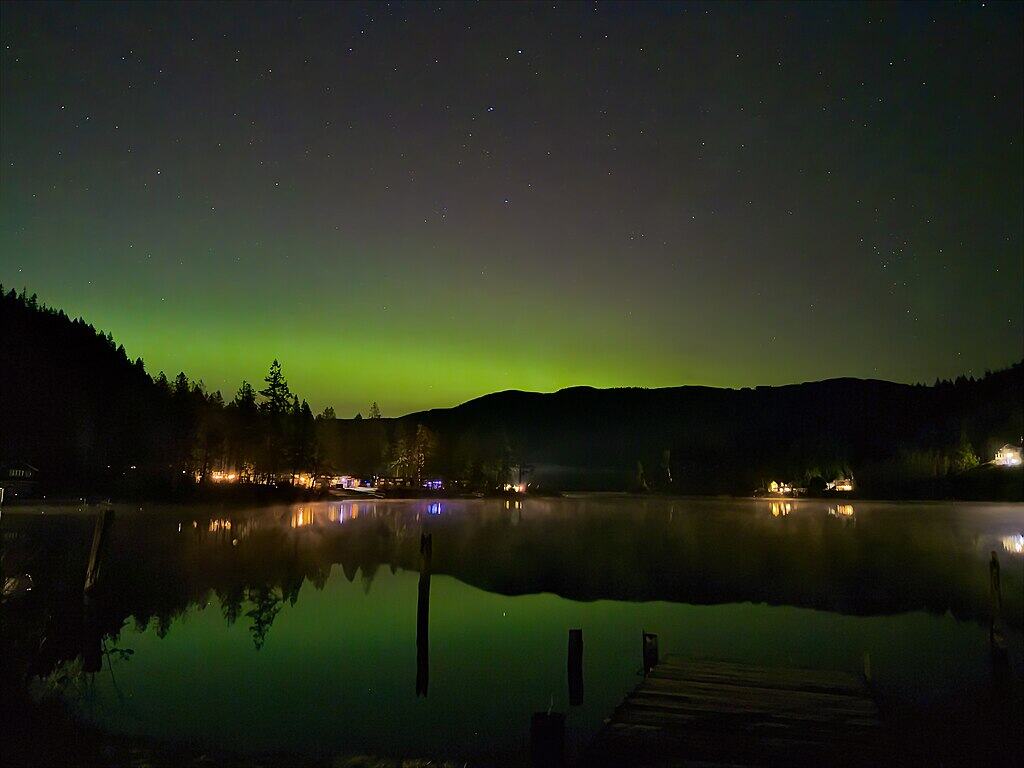

4. What the Lights May Look Like

Unlike vivid curtains seen in polar regions, auroras at lower latitudes often appear subtler. Observers may notice pale green glows, vertical light pillars, or faint pink edges caused by oxygen emissions at 100–300 kilometers altitude. Red tones, produced by higher-altitude oxygen above 200 kilometers, become more common during stronger storms. Cameras can capture colors invisible to the naked eye, sometimes revealing brightness levels 2–3 times stronger in photos. Motion may appear slow, with gentle waves rather than dramatic rippling curtains.

5. Weather and Visibility Factors

Clear skies are as important as solar strength. Even thin cloud cover can block up to 90% of auroral visibility. Ideal conditions include low humidity, minimal moonlight, and unobstructed northern horizons. A half-moon or brighter can reduce contrast by nearly 40%, making faint auroras harder to detect. Snow-covered ground, however, can improve ambient light reflection slightly. Wind speed and temperature matter less for visibility but affect comfort, as many viewers spend 30–90 minutes outside waiting for activity peaks.

6. How Rare This Opportunity Is

Auroras visible this far south are uncommon, occurring only a few times per solar cycle. The current solar cycle, Cycle 25, is approaching its projected maximum between 2024 and 2026, increasing event frequency. However, storms capable of pushing auroras into mid-latitude U.S. states happen roughly 1–3 times per year at most. This makes Monday’s potential display notable, especially for casual observers who may never have seen auroras before. Missed opportunities can mean waiting months, or even years, for similar conditions to align again.