We may earn money or products from the companies mentioned in this post. This means if you click on the link and purchase the item, I will receive a small commission at no extra cost to you ... you're just helping re-supply our family's travel fund.

Pitcairn Island sits in the South Pacific so far from major routes that distance becomes part of daily identity. There is no airport, no quick supermarket run, and no anonymous street life. The population is often described as around 40 people, and that scale changes everything from governance to groceries. Life works through planning, shared labor, and social trust built over years. Isolation here is not romantic background. It is the core system that shapes time, choices, and community resilience every single week.

A Community Small Enough to Know Every Family

On Pitcairn, population is not just a statistic. It defines how society functions. With around 40 residents, people do not simply recognize each other. They depend on each other for services, coordination, and emotional stability in a place with limited outside support. News travels quickly, help is personal, and disagreements cannot be avoided through distance. That social closeness can feel comforting or intense depending on the day, but it is always real. In a micro-community, cooperation is not idealism. It is infrastructure.

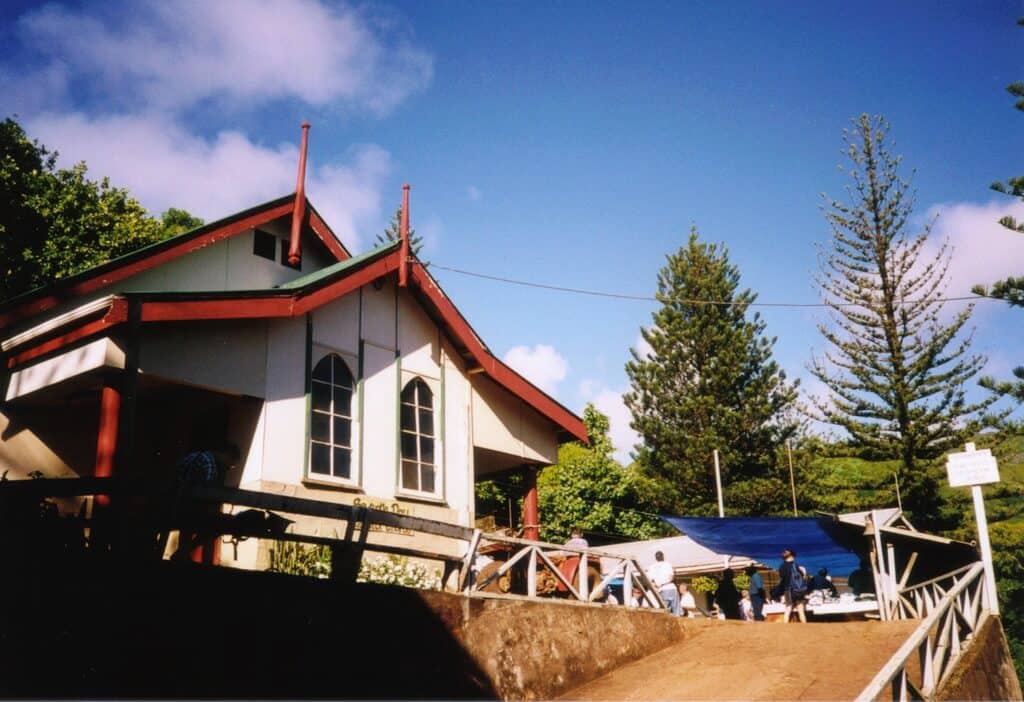

One Settlement, One Shared Civic Space

Adamstown is the island’s only settlement, which means nearly all civic life happens in one compact area shaped by steep terrain and ocean weather. There is no secondary town, no backup district, and no suburban buffer where systems can shift quietly. When a public issue appears, everyone sees it and often helps address it. Schools, administration, roads, and household life are tightly linked. That concentration creates unusual clarity: people know where decisions are made, who carries responsibility, and how quickly local conditions can change.

No Airport Means the Sea Controls the Schedule

Pitcairn has no runway, so access depends on ships and careful transfer logistics from other Pacific points, often through Mangareva. Travel is slow, weather-sensitive, and planned far in advance. This affects more than tourism. It shapes medical access, mail, spare parts, and family movement on and off the island. A missed connection is not a minor inconvenience in a place like this. It can shift household plans for weeks. Maritime timing sets the island’s rhythm, and everyone learns to work within that rhythm instead of resisting it.

Governance Feels Immediate and Personal

Pitcairn is a British Overseas Territory, but local governance is lived face-to-face in a very small social field. Policy is never abstract because officials and residents interact constantly in daily life. Decisions about infrastructure, services, or community rules can affect neighbors by the next morning, so accountability is direct and visible. That proximity can strengthen trust when processes are clear, yet it also demands emotional maturity when disagreements happen. In larger places, institutions absorb tension. Here, people do, and they must keep working together after every difficult conversation.

Nature Is Powerful but Never Casual

The island and its surrounding waters are ecologically significant, yet nature here is not a leisure backdrop. Terrain is steep, ocean conditions can shift quickly, and weather can disrupt plans without warning. Residents learn to read local conditions closely and make conservative decisions, especially around travel and coastal activity. Respect for environment is both cultural and practical because mistakes carry higher consequences when response options are limited. Life on Pitcairn is shaped by beauty, yes, but even more by restraint, patience, and local knowledge developed over time.