We may earn money or products from the companies mentioned in this post. This means if you click on the link and purchase the item, I will receive a small commission at no extra cost to you ... you're just helping re-supply our family's travel fund.

Cicadas fade, porch lights warm, and the air thickens with memory. Across the American South, towns hold beauty and ruin in the same frame, where magnolias shade courthouse steps and cemeteries tilt toward the river. Writers and filmmakers borrowed these corners for monsters that look a lot like grief, guilt, or history refusing to sleep. The architecture whispers, the soil remembers, and a single street can hold three centuries at once. Here are places where story and setting keep each other honest after dark.

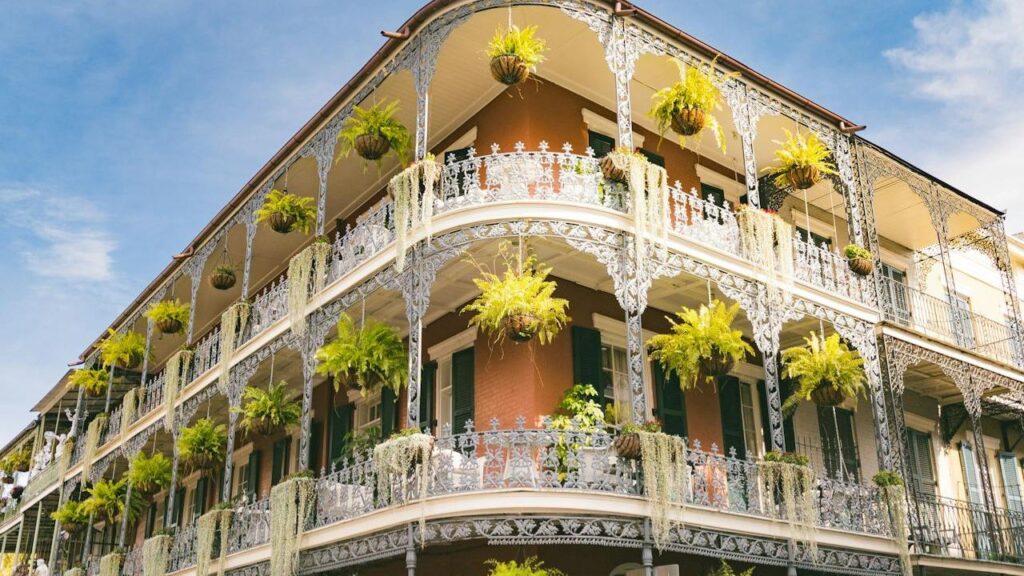

New Orleans, Louisiana

Balconies drip ironwork over streets that never quite go quiet. Anne Rice lifted Garden District parlors and St. Louis Cemetery’s stacked tombs into “Interview with the Vampire,” where immortals stroll beneath gaslight and live oaks. Voodoo markets, second lines, and shuttered courtyards give the city a pulse that feels older than its music. In New Orleans, the Gothic is social, domestic, and ceremonial, a velvet parlor where the past asks for another hour.

Savannah, Georgia

Spanish moss frames squares that turn moonlight into rumor. John Berendt’s “Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil” is true crime dressed like a ghost story, and the city leaned in, balancing grace with mischief. Colonial lanes, Colonial Park Cemetery, and riverside warehouses lend a stage to legends told as politely as tea. Savannah’s beauty sharpens the strangeness; marble angels and brick alleys insist that elegance and unease share the same address.

Oxford, Mississippi

William Faulkner reimagined Oxford as Jefferson, seat of Yoknapatawpha County, where family names and ruined mansions freight every gesture. “A Rose for Emily” made a parlor a mausoleum and gossip a Greek chorus. Red clay, courthouse columns, and oak shade give the place its stubborn gravity. The town speaks in slow vowels and archival guilt, turning ordinary rooms into reliquaries. Here, the horror is memory that never quite agrees to be buried.

Milledgeville, Georgia

Flannery O’Connor wrote from Andalusia Farm, where peacocks and prayer clashed with car wrecks and revelation. Her stories—“A Good Man Is Hard to Find,” “The Life You Save May Be Your Own”—bend the holy toward the grotesque with sly clarity. Downtown storefronts, country chapels, and sunstruck pastures feel complicit, as if grace and violence attend the same picnic. The town’s calm surface only deepens the shock when the world tips and refuses to right itself.

Sullivan’s Island, South Carolina

Fort Moultrie faces a shoal of wrecks and stories. Stationed here as a young private, Edgar Allan Poe scavenged tides and cottages for “The Gold-Bug,” while the sea air salted later tales with dread. Sand paths, palmettos, and battery walls arrange a set that asks what the ocean returns besides shells. The island’s neat porches and blown-open horizons make reason feel fragile. That tension gave Poe his key: beauty courting ruin in plain sight.

Key West, Florida

Pastel cottages hide a harder legend: Robert the Doll, a century-old curiosity tied to whispers that sailed into horror cinema. The island’s graveyard stacks coral rock and clipped epitaphs above a water table that refuses neat endings. Hemingway’s house, quiet lanes, and sunset crowds create a carnival of light that throws long shadows. Key West’s sweetness makes its chills stranger, as if paradise itself invited a dare and took it seriously.

Eureka Springs, Arkansas

Victorian hotels climb Ozark stone like elaborate birdcages. The Crescent Hotel sits tallest, a grand dame with a file of hard stories that fed novels, tours, and film crews. Curved streets, limestone springs, and painted gingerbread build an operatic backdrop where whispers travel efficiently. Night wraps the town in theater velvet, and every lamp becomes a spotlight. Even laughter in the dining rooms sounds rehearsed, as though the chorus knows the darker third act.

Clarksdale, Mississippi

The Delta’s flat horizon meets a rumor at the crossroads, where the blues taught a bargain no contract could hold. While not born as horror, the Robert Johnson legend infected fiction and film with Southern dread—a pact, a shadow, a song that costs too much. Tin-roof juke joints, neon, and freight trains provide the percussion. Clarksdale makes the uncanny sound like music, which may be why the story never stops playing.

Charleston and Mount Pleasant, South Carolina

Across the Cooper River, suburbs and barrier islands carry their own hauntings. Grady Hendrix grew up nearby and later set “My Best Friend’s Exorcism” in the 1980s lowcountry, trading azaleas and cul-de-sacs for demonic rumor. Charleston’s church spires, alleys, and tidal creeks supply an elegance that collapses nicely into panic. The contrast is the point: debutante daylight, then something knocks at the screen door long after the porch light dies.