We may earn money or products from the companies mentioned in this post. This means if you click on the link and purchase the item, I will receive a small commission at no extra cost to you ... you're just helping re-supply our family's travel fund.

Some travel sites feel like museums. Christian music landmarks often feel like living rooms, places where a hymn was first sung, a choir still rehearses, or an organ note hangs in the air long after visitors leave. Across cathedrals, chapels, and a few modern institutions, sacred sound has shaped cities as surely as stone and stained glass. These stops draw pilgrims, music lovers, and the simply curious, offering quiet proof that faith traditions keep evolving through melody, memory, and community.

Ryman Auditorium, Nashville, Tennessee

The Ryman opened in 1892 as the Union Gospel Tabernacle, built after Thomas Ryman’s conversion at a revival, and the room still carries a church-born gravity that modern venues rarely imitate. Pews face a stage that has hosted gospel quartets, hymn-singing crowds, and later the Grand Ole Opry, so sacred music never feels like an add-on to the building’s legend. During daytime tours, guides linger on the tabernacle years, and visitors often notice how the hush survived every reinvention, turning applause into something that feels almost like congregational response and leaves an aftertaste in the air, even when the calendar says concert night.

Source.

Cowper And Newton Museum, Olney, England

In the market town of Olney, the Cowper and Newton Museum keeps the backstory of “Amazing Grace” grounded in specific rooms, streets, and parish habits rather than myth. Rev. John Newton wrote the hymn while serving as curate nearby, and it later appeared in “The Olney Hymns,” a local project that paired faith with plainspoken language meant to be sung by ordinary voices. The stop is modest, yet the effect is outsized: a global anthem traced back to friendship, doubt, and daily ministry, with artifacts that make the famous words feel newly human and surprisingly close and shows how a town-sized hymnbook can travel farther than anyone planned.

Source.

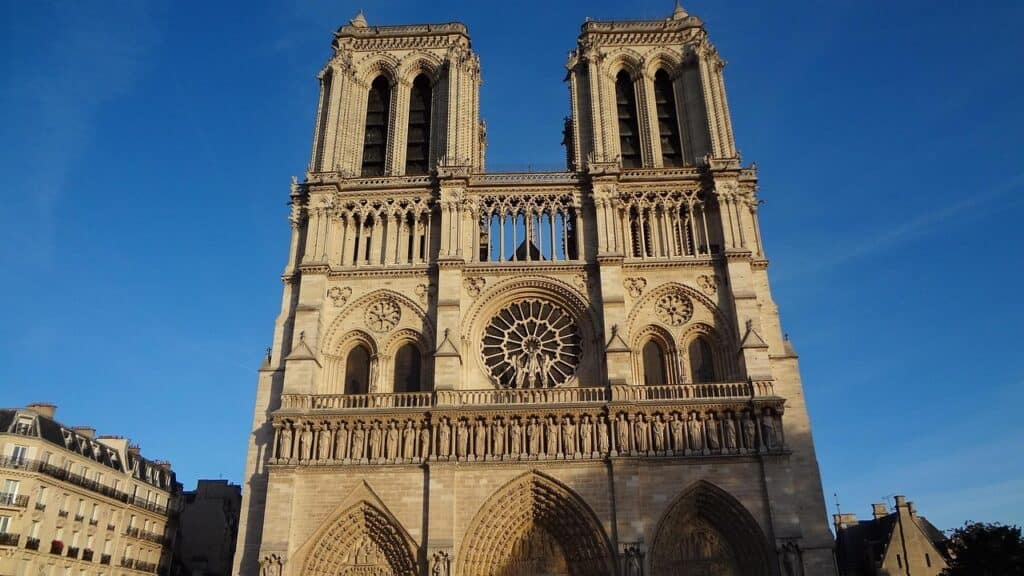

Notre-Dame De Paris, Paris, France

Notre-Dame’s reopening on Dec. 7, 2024, restored more than a skyline icon; it returned a cathedral built for chant, organ, and long acoustics that carry prayer far beyond a single pew. After the 2019 fire, the renewed interior makes sacred sound feel newly present, even when the building is simply breathing between services, tourists, and the slow movements of clergy and staff. Visitors arrive with fresh memory of loss and rebuilding, and many leave listening differently, as if the building’s first purpose is still to hold music gently in the air and make time feel slower while choirs and organs reclaim the space without rushing the mood now.

Source.

Westminster Abbey, London, England

Westminster Abbey treats sung prayer as a daily craft, offering choral services that range from ancient chant to newly written anthems, held in the same stone that carries royal history. Evensong, shaped by “The Book of Common Prayer,” turns late afternoon into a calm ritual of psalms, canticles, and anthems, and the Quire becomes less a tourist destination than a working chapel. Travelers come for monarchs and monuments, then stay for music that feels unforced and current, proof that tradition can be both disciplined and alive, not merely preserved behind velvet ropes with free services that turn visitors into listeners, without fuss at all.

Source.

St Paul’s Cathedral, London, England

At St Paul’s, Choral Evensong is treated as a treasure, a service of sung Evening Prayer drawn from the 1662 “Book of Common Prayer” and shaped to fit the cathedral’s vast interior. The choir’s lines land softly under the dome, where resonance smooths edges and lets familiar texts bloom into something spacious, meditative, and surprisingly intimate. Many visitors arrive for architecture and views, yet the music becomes the memory, because it offers a slow, held moment inside a city that usually asks for speed, noise, and constant decisions and a sense that London’s sacred music tradition is not a museum piece, but a weekly practice in public.

Source.

St Mark’s Basilica, Venice, Italy

St Mark’s Basilica helped invent a sound made for its own architecture, as choirs answered each other from opposing lofts in the Venetian polychoral style, turning worship into spatial conversation. Composers such as Adrian Willaert wrote antiphonal sacred music for San Marco, and Giovanni Gabrieli later pushed the spectacle with bold dynamics and specified instruments that filled the basilica with brass and echo. Inside the mosaicked nave, the idea becomes physical: music moves like light across stone, and visitors can almost hear why this building taught Europe that sacred sound could be dramatic without losing devotion in the echoing nave.

Source.

Sistine Chapel, Vatican City

The Sistine Chapel Choir is the Pope’s personal choir, formally constituted under Pope Sixtus IV in the late 1400s, with roots reaching back to early Christian singing schools. It remains a storied sacred ensemble, known for unaccompanied repertoire that carries Renaissance polyphony into modern liturgies and keeps the focus on the human voice alone. Visitors arrive for Michelangelo, yet the chapel’s deeper identity is musical and devotional, a room designed for voices that make silence feel meaningful rather than empty, and for prayer that arrives through harmony where the choir’s history makes the famous ceiling feel secondary for a moment.

Source.

St Thomas Church, Leipzig, Germany

St Thomas Church in Leipzig keeps sacred music tied to daily discipline, not nostalgia, through the Thomanerchor, a boys’ choir founded in 1212 and still central to worship. Johann Sebastian Bach served here as Thomaskantor from 1723 to 1750 and is buried in the church, a fact that turns a famous name into a physical presence beneath the floor. Travelers step into a Gothic hall church and sense continuity, where rehearsals, services, and the city’s musical memory blend into one living practice that has never fully stopped as motets and cantatas continue to mark weeks on the calendar, giving the city a steady pulse beyond tourism seasons here.

Source