We may earn money or products from the companies mentioned in this post. This means if you click on the link and purchase the item, I will receive a small commission at no extra cost to you ... you're just helping re-supply our family's travel fund.

If the Seven Wonders had survived intact, they would not feel like ruins at the edge of memory. They would feel immediate: engineered for awe, scaled to overwhelm, and placed where light, water, and ritual amplified every surface. Historians know some details well and others only through ancient descriptions, which makes any modern reconstruction part evidence and part careful imagination. Still, the outlines are powerful. These seven landmarks would likely read as living megastructures today, each one shaped by local climate, materials, and the political ambition that built it in the first place.

Great Pyramid Of Giza As A Blinding Geometric Peak

If seen in original form, the Great Pyramid would look less sandy and rugged than it does now. It was once faced with smooth white Tura limestone that reflected sunlight, creating a bright, almost polished exterior rather than stepped stone. At full height, it rose higher than today’s profile, likely topped by a pyramidion, and sat within a ceremonial complex that tied monumentality to processional movement. In modern terms, it would read like a perfectly resolved architectural object: sharp edges, controlled symmetry, and a luminous skin engineered to dominate the horizon.

Statue Of Zeus At Olympia As A Gold And Ivory Interior Colossus

The statue at Olympia would not stand outdoors like many modern icons. It would dominate an enclosed temple interior, seated, towering, and coated in chryselephantine surfaces, gold and ivory over a crafted core, with painted and carved details around it. In current terms, it would feel like entering a purpose-built theater of power, where scale, material, and ritual choreography were inseparable. Light filtering through the temple would strike metal and ivory in shifting bands, giving the figure a living presence. It would be less a sculpture in a room and more an environment of controlled reverence.

Temple Of Artemis At Ephesus As A Marble Civic Stage

If rebuilt to its grand classical form, the Temple of Artemis would appear as a vast marble platform ringed by columns, with sculptural programs, broad stair approaches, and a footprint that could still hold visual authority against modern public buildings. It was repeatedly rebuilt in antiquity, and the celebrated version was famed for size and ornament rather than fortress mass. Today it would likely read as both sacred architecture and civic stage, an urban anchor where religion, economy, and identity converged. The whiteness of stone, rhythmic colonnades, and open forecourt would make it feel formal yet surprisingly permeable.

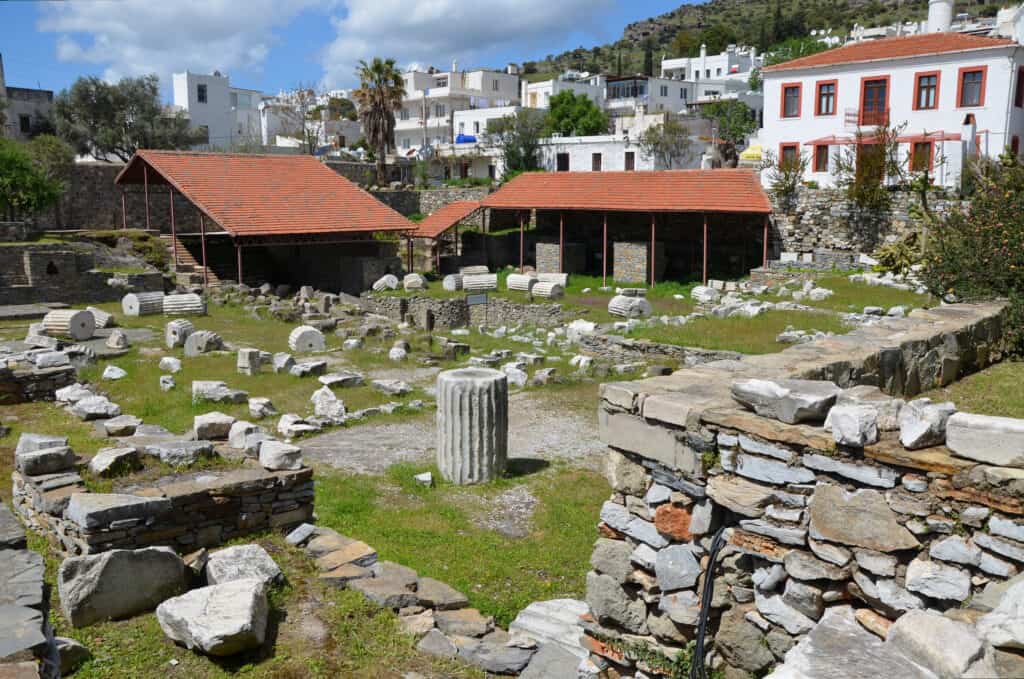

Mausoleum At Halicarnassus As A Hybrid Of Tomb And Monument

The Mausoleum would probably look startlingly modern in composition: a tall podium, colonnaded middle zone, stepped roof, and sculptural crown, combining Greek, Anatolian, and Egyptian influences into one coherent statement. It gave the world the word mausoleum for a reason. If standing today, it might be read as a prototype for state memorial architecture, less tomb than narrative machine in stone. Relief carvings would wrap the structure with political storytelling, while the vertical layering would pull the eye upward from civic scale to symbolic eternity, a deliberate fusion of grief, status, and design intelligence.

Colossus Of Rhodes As A Bronze Coastal Landmark

The Colossus would likely appear as a massive bronze figure on a harbor promontory rather than straddling the port entrance, a pose widely regarded as technically unlikely for the period. At roughly 33 meters, it would still command attention in any modern waterfront skyline, especially with sun and salt weathering the metal into a deep, irregular patina. Built to celebrate military survival, it was civic messaging at maximum scale. In a contemporary setting, it would function like a national symbol and navigation marker at once, where political memory and maritime identity meet the sea.

Lighthouse Of Alexandria As A Vertical Signal City

The Pharos of Alexandria would feel instantly legible today: a multi-tiered tower built for visibility, navigation, and state prestige, rising above the harbor with fire and reflective systems guiding ships after dark. Ancient descriptions place it among the tallest man-made structures of its time, and in modern terms it would sit somewhere between infrastructure and monument. By day, it would anchor the skyline; by night, it would choreograph movement on water. Its real power would be functional beauty, proving that utility, symbolism, and architectural drama can occupy the same vertical form.