We may earn money or products from the companies mentioned in this post. This means if you click on the link and purchase the item, I will receive a small commission at no extra cost to you ... you're just helping re-supply our family's travel fund.

October sharpens memory, and the old witchcraft stories feel close to the skin. Courtrooms turned into theaters, ponds became tests, and quiet greens absorbed fear that outlived verdicts. Visiting these places adds texture to a history often reduced to a headline. Names return to the record, families step out of footnotes, and law reveals its blind spots. What this really means is that commemoration matters. Stones, plaques, and small museums carry hard lessons with steady focus, inviting careful attention over spectacle.

Windsor, Connecticut: Memorial to Alse Young and Lydia Gilbert

Long before Salem, Windsor recorded executions for witchcraft in 1647 and 1654. The town green now holds engraved bricks that name Alse Young and Lydia Gilbert, returning dignity to lives once crushed by rumor. The memorial sits in everyday space where school drop offs and Saturday errands pass over history that refuses to stay quiet. It asks for reflection without theatrics, a quiet correction set into common ground that argues for remembrance as a public duty, not a seasonal thrill.

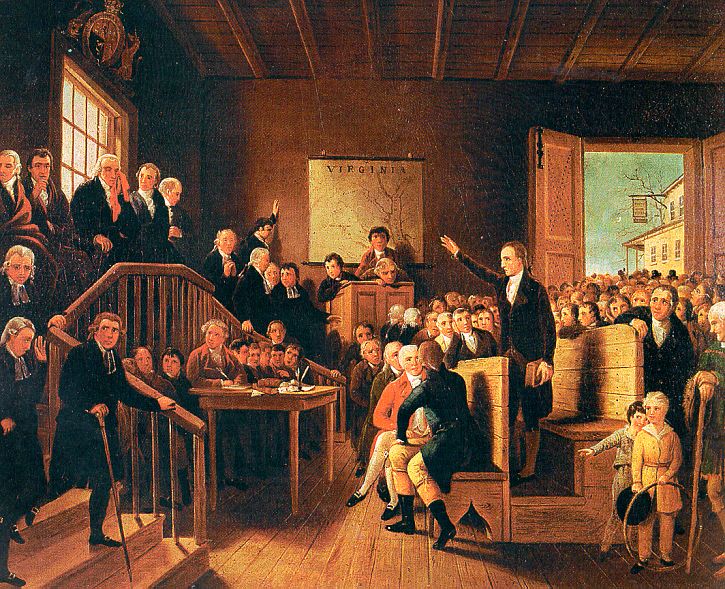

Hartford, Connecticut: The 1662–63 Witch Panic

In the early 1660s, Hartford wrestled with accusations that shaped how courts across New England handled suspicion. Depositions, contested confessions, and neighbor quarrels built a vocabulary of fear later echoed in 1692. Modern streets hide the old meetinghouse grid, but the record remains detailed and stubborn. Read on site, the story becomes a chain of choices by ministers, magistrates, and townsfolk who could not agree on proof. The city’s bustle adds contrast, and the paper trail holds its line.

Fairfield, Connecticut: Town Green and Edwards Pond

Fairfield’s trials reached a climax in Oct. 1692 when Mercy Disborough and Elizabeth Clawson faced judgment after the crude water test at Edwards Pond. The town green looks peaceful now, edged by churches and tidy paths. Local maps and exhibits point back to a crowd that weighed gossip against a human life. The setting makes a simple point with force. Ordinary landscapes can host extraordinary damage, then ask new generations to define justice with clearer rules and steadier hands.

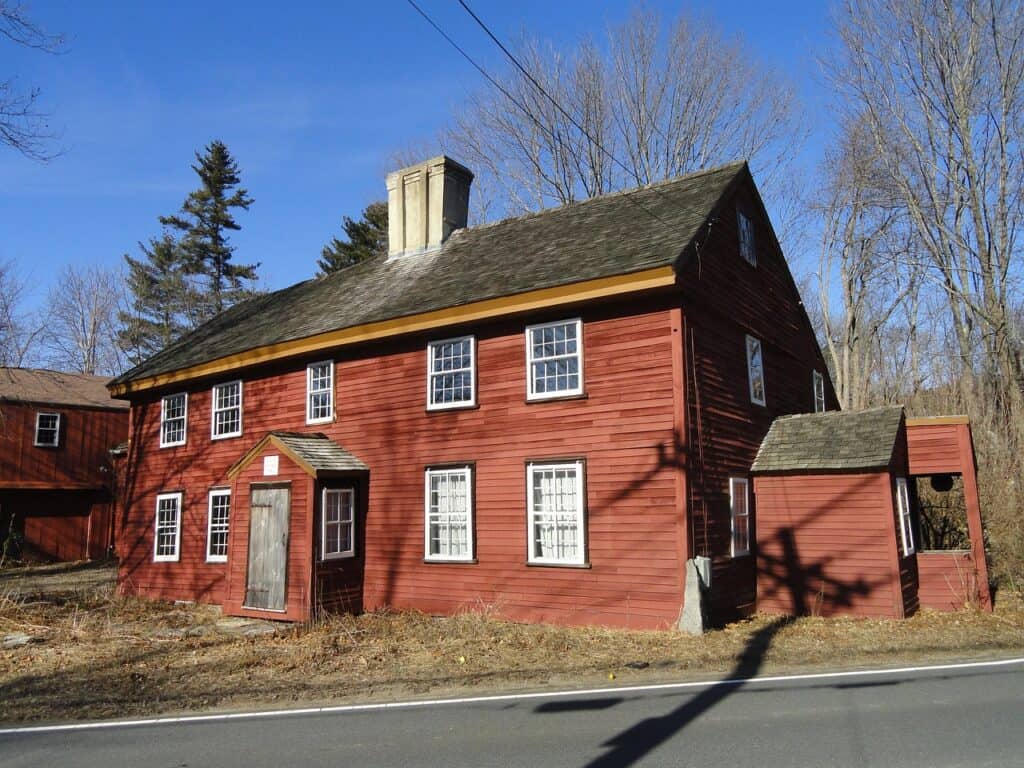

Stamford, Connecticut: A Measured 1692 Response

Stamford’s cases began with a servant’s visions that rippled through households, yet the court pressed hard on evidence rather than theater. That restraint matters, because panic was not inevitable, even in 1692. Original roads still trace the seventeenth century plan, and the Hoyt Barnum House anchors the story in place. Standing here reframes the year everyone quotes, showing how outcomes depended on who sat in judgment, how they listened, and when they chose to stop the spread of fear.

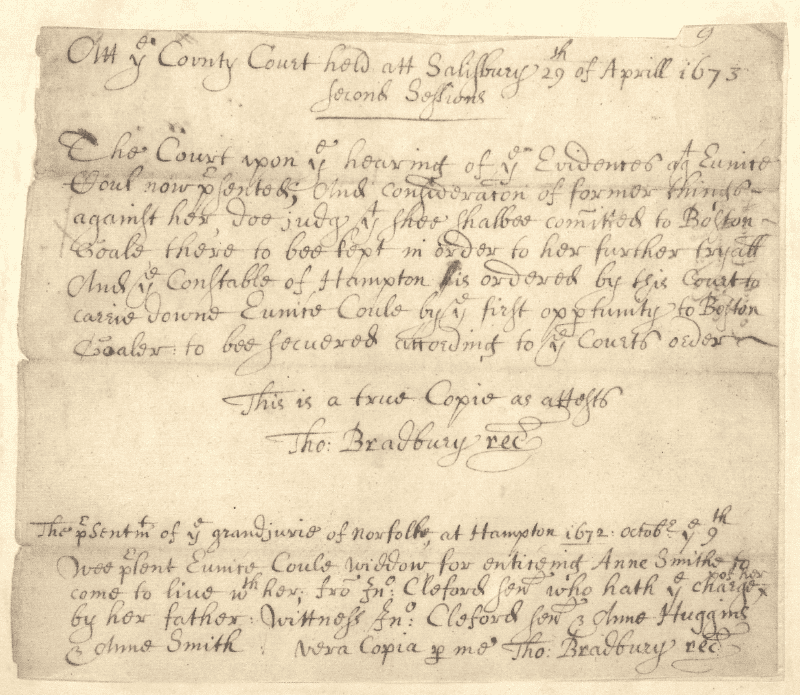

Hampton, New Hampshire: Goody Cole Remembered

Eunice Cole spent years in prison and years under suspicion, a neighbor recast as menace. A rough stone near the Tuck Museum now stands for an apology, late and imperfect but public. The gesture does not erase what she endured, yet it pulls her name from rumor and sets it where anyone can read it. The memorial’s spareness suits a reputation that outlasted verdicts. The smallness is the point. Memory does not need spectacle to be felt or to guide repair.

Andover, Massachusetts: Panic Across Parish Lines

Andover saw more accused than any community in Essex County during 1692. Family networks, parish boundaries, and sudden confessions pushed numbers higher than the better known trials to the east. Cemeteries and farm lanes still connect those names, turning a map exercise into a neighborhood reckoning. The lesson is clear and difficult. Fear travels through kin, and reversing course takes longer than the first accusation. Walking the grid shows how communities fracture, then slowly and unevenly learn to mend.

Boston, Massachusetts: Ann Hibbins Before 1692

Boston executed Ann Hibbins in 1656, a case tangled with status, church discipline, and local politics. The record complicates any tidy timeline that begins and ends with Salem. It takes work to imagine the wooden streets and crowded galleries where verdicts landed, but the documents point to real addresses and voices. The echoes are practical as much as moral, showing how procedures harden, travel, and later face review. Boston’s archives make the lesson plain. Process always shapes outcome.

Boston, Massachusetts: Goody Glover in the North End

Ann Glover, an Irish immigrant and Catholic, was hanged in 1688 after a prosecution shaped by difference as much as harm. A modest plaque in the North End keeps her visible amid cafes and brick facades. The block is loud and ordinary, which is the point. Her name meets daily foot traffic and holds ground, a bronze rectangle that asks for patience and a slower way of walking a familiar street. Memory shares space with errands and still changes the route.

Springfield, Massachusetts: The Parsons Affair

In 1651 and 1652, Springfield confronted the Parsons case, a knot of grievances, illness, and courtroom struggle. The story often gets swallowed by later events, yet local archives and exhibits restore its scale. Objects, timelines, and testimony sketch how fear found a foothold on the Connecticut River. Seen locally, the episode stops being a preface and becomes an early chapter that shaped what came next. The museum context gives faces to names and turns legal phrases into lives.

Virginia Beach, Virginia: Grace Sherwood and Witchduck Creek

Grace Sherwood was tried by water in 1706, the rare Virginia case that left deep marks on the landscape. Witchduck Road, a statue, and the Ferry Plantation House tell how a farmer endured humiliation, returned to work, and outlived her judges. Place names carry memory without pageantry. The creek looks ordinary and calm, and that ordinariness turns spectacle into context. It reads as a life resumed, a community learning slowly, and a standing reminder that rituals can become warnings.

Delaware County, Pennsylvania: Margaret Mattson’s Trial

In 1683, Margaret Mattson stood before William Penn’s court after accusations that would have spiraled elsewhere. She was not condemned, and that matters. Markers and local histories preserve a hearing that stressed evidence over theater and kept the colony from repeating harsher patterns. The episode widens the map of witchcraft law and shows how legal culture, not only rumor, determined who survived a season of fear. The restraint can be read on the landscape, modest and firm.

New York, New York: The Halls at the Court of Assizes

Ralph and Mary Hall were tried in 1665 after charges that began in Setauket reached the city’s high court. The proceeding tied English law to a growing municipal center, proof that colony and empire shared the same anxieties. Archives and walking routes trace the old city hall, now absorbed by modern blocks. Paper trails give the trial a street address and turn abstract law into civic memory. The city’s layers let the past sit inside the present.