We may earn money or products from the companies mentioned in this post. This means if you click on the link and purchase the item, I will receive a small commission at no extra cost to you ... you're just helping re-supply our family's travel fund.

You came for clear water and quiet, but what you want most is a place that chooses wildlife over welcome drinks. These islands do exactly that. Visitor caps, permit systems, and community rules keep ecosystems ahead of marketing. You trade infinity pools for reef etiquette, and turnstiles for trail briefings. Bring patience, a soft footprint, and respect for local science. What you get back is rare: habitats that still breathe on their own timetable.

Aldabra Atoll, Seychelles

A UNESCO stronghold ringed by turquoise channels, Aldabra hosts the world’s largest population of giant tortoises and a lagoon alive with sharks and rays. Access is by expedition ship or research permit, and landings are tightly controlled by the Seychelles Islands Foundation. Guides set the pace, group sizes stay small, and boot prints stop short of nesting sites. You are here to witness an ecosystem working, not to shape it to your plans.

South Georgia, South Atlantic

Here the beach is a living conveyor belt of king penguins, fur seals, and elephant seals, backed by glaciers. Every visitor scrubs boots and gear to strict biosecurity standards before stepping ashore. Trails are zoned, wildlife buffers are nonnegotiable, and numbers are capped per landing. You move slowly, eyes up, camera down until an officer nods. The payoff feels elemental, like the island invited you to observe and then asked you to leave it whole.

Lord Howe Island, Australia

This crescent of jungle and reef limits visitors to about 400 at any time. The community led a rat eradication that brought the woodhen back from the brink, and trails like Mount Gower require licensed guides to protect fragile cloud forest. You pedal bikes, not rental cars, and fall asleep to shearwaters, not nightlife. On Lord Howe, conservation is not a slogan. It is a daily practice that visitors plug into for a week, then carry home.

Tubbataha Reefs, Philippines

In the Sulu Sea, this marine park is open only to liveaboards in a short season, with rangers stationed year round on a tiny sand cay. Anchoring is banned, moorings are fixed, and dive briefings feel like mini biology classes. Currents sweep in sharks, manta rays, and vast coral gardens that look untouched because they are treated that way. You log dives, swap IDs of wrasses and snappers, and leave no mark beyond bubbling exhale.

Cocos Island, Costa Rica

A volcanic peak adrift in the Pacific, Cocos is all water life and waterfall mist. No hotels, no casual drop-ins, only multi-day liveaboards with supervised diving around hammerhead cleaning stations. Rangers enforce no-take rules, and inspections are real. Boats keep distance from shore, dives stick to strict codes, and wildlife gets the full stage. If you want luxury, bring a good wetsuit and the kind of patience that big marine life demands.

Fernando de Noronha, Brazil

Visitor numbers are controlled, and a daily environmental fee nudges stays shorter and more thoughtful. Trails run on timed entries, beaches like Sancho Bay have ladders and quotas, and snorkeling spots have stewards who will call you out for chasing turtles. You go for spinner dolphins at dawn, nap through the hot hours, then wander simple streets as trade winds cool. The island feels protected because locals insist on it.

Pitcairn Islands, Pacific

One of the world’s smallest communities sits inside one of the largest marine reserves, and the sea sets the rules. There is no resort, only home stays, a supply ship every few weeks, and trails that drop to coves where coral gardens start a few steps from shore. Visitors help by following fishing limits, scrubbing gear, and packing out anything they brought in. On Pitcairn, isolation protects as much as policy does.

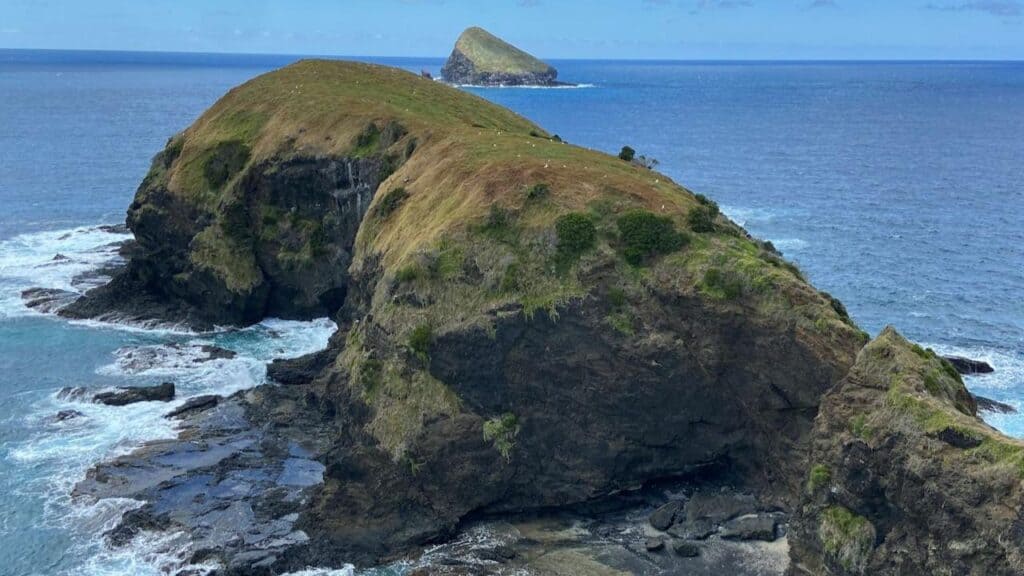

Skellig Michael, Ireland

A jag of rock rising from the Atlantic, Skellig allows a short daily window for small boats when seas cooperate. Landings are limited, and the climb to the monastic beehive huts is steep and unguarded. Puffins whirl like confetti in early summer, and wardens keep humans off ledges where burrows run close. You leave with salt in your hair and a quiet understanding that wild places set terms, not timetables.

Gorgona Island, Colombia

A former prison turned national park, Gorgona limits visitors and keeps reefs and rainforest under vigilant eyes. Rangers manage dive sites like Yundigua and Montañita, while humpbacks sing offshore from July to Oct. Trails cross poison dart frog habitat and end at beaches where sea turtles nest. Boats and feet remain on approved routes, and guides are not optional. The result is a rare mix of tropical forest and Pacific blue that still feels intact.

Santa Barbara Island, USA

The smallest of California’s Channel Islands demands a boat ride and a willingness to walk. There are no services, only cliff-top trails, sea lions in raucous colonies, and seabird rookeries fenced against careless steps. Restoration work is ongoing, and closures protect nesting seasons. Campers pack out everything and study weather like a sailor. The island’s luxury is space, wind, and the company of storm petrels after dusk.

Skomer Island, Wales

Skomer is puffin central in spring, but entry is capped and ferry crossings sell out fast. Paths keep feet on firm ground and off burrows, wardens answer questions, and human noise stays low. You watch puffins shuffle past your boots with beaks full of sand eels, then step back as kittiwakes sweep cliffs. The island closes completely in winter to give birds and seals the stage. Conservation here is simple: give wildlife time and room.

Tristan da Cunha, South Atlantic

The world’s most remote inhabited island does not court visitors. You arrive by ship after days at sea, then step into a community that declared the surrounding waters a vast marine reserve. Biosecurity is personal. Boots are scrubbed, gear is checked, and walks outside the settlement respect nesting grounds and weather that can turn in minutes. You leave with stamps in a passport and a clearer sense of what guardianship looks like in practice.