We may earn money or products from the companies mentioned in this post. This means if you click on the link and purchase the item, I will receive a small commission at no extra cost to you ... you're just helping re-supply our family's travel fund.

Some shorelines look friendly right up until the water proves otherwise. The risk is rarely dramatic at first; it is usually physics, local geography, and a few conditions that punish casual decisions. Rip currents form on postcard days. Shorebreak hits hardest when the water seems shallow. Wildlife shows up where food and warm water meet. In remote places, the real danger is how long help takes to arrive. The safest beach days come from paying attention to flags, forecasts, and the quiet truth that oceans do not negotiate.

Hanakapiai Beach, Kauai, Hawaii

Hanakapiai rewards the Kalalau Trail with a wide, golden shoreline, then quietly removes the safety net. State guidance says swimming is not recommended because rip currents and wave patterns can shift fast and pull hard, even when the surface looks gentle, the sun is out, and the water feels like a prize after miles on foot. The isolation matters as much as the water: the beach sits beyond the road, stream crossings change with rain, cell service can be spotty, and the return trek turns a small emergency into a long, exhausting operation that starts with simply getting word out.

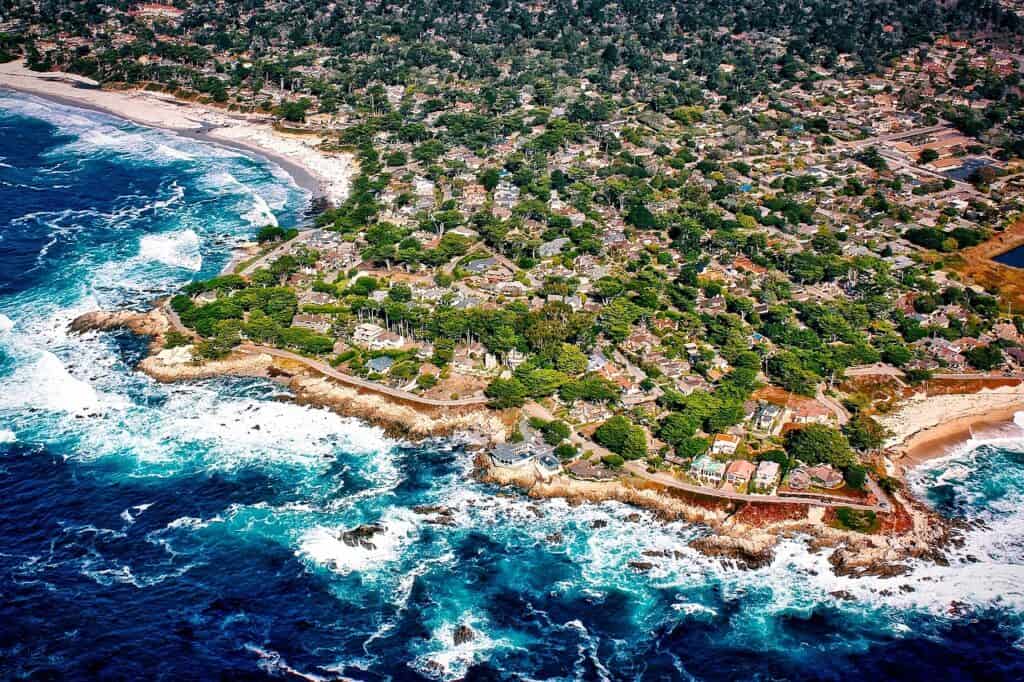

Monastery Beach, Carmel-by-the-Sea, California

Monastery Beach looks calm from the sand, but the bottom drops steeply and the cove can stack hazards in one place. A few steps past the break can mean deep water, cold shock, and a fast pull seaward, especially when swell wraps into the bay and backwash surges under the next wave, knocking knees and stealing breath. Locals treat it like technical water, timing entries and exits with care, because the undertow can pin feet, visibility can turn milky, and the beach falls away before panic has time to register, turning bravado into pure fatigue.

Sandy Beach, Oahu, Hawaii

Sandy Beach is famous for shorebreak, the kind that breaks directly on the sand and turns a normal wave into sudden impact. Honolulu Ocean Safety warns that shorebreak is unpredictable and can cause serious head, neck, and spinal injuries, even when the water seems shallow, the swell looks playful, and the crowd makes it feel routine. Reef and sandbars reshape the break hour to hour, so a safe-looking set can be followed by a hard dumpy wave, and the smartest move is to watch the rhythm for several sets, follow flags, and let lifeguards set the tone.

New Smyrna Beach, Florida

New Smyrna feels easy: warm water, steady waves, and a laid-back strip of sand that fills up fast on bright days. It also sits in Volusia County, a long-running hotspot in shark-bite tracking, largely because crowds share shallow water with baitfish and small sharks near inlets, sandbars, and the choppy seams where fish move. Add shifting channels after storms, rip-current days that arrive under blue skies, and summer lightning that builds fast, and the risk becomes layered enough to reward disciplined choices, clear timing, and attention to posted flags. Florida Museum

Praia do Norte, Nazare, Portugal

Praia do Norte is built for watching, not drifting, because the sea here can change character in a single set. Nazare’s canyon amplifies Atlantic swells, creating famous winter surf and strong currents that can linger even when the horizon looks calm and the shoreline feels strangely peaceful. Rips can run beside the lineup like rivers, and a surprise surge can shove swimmers into a tiring fight with the shoreline, so locals keep a clear boundary between spectator sand and serious water, especially when wind starts stacking lines offshore.

75 Mile Beach, K’gari, Australia

K’gari’s ocean side runs for miles like an open invitation, which is exactly why it catches people off guard. Queensland park updates warn that sharks and marine stingers are present offshore and that swimming is not recommended along the eastern beaches, even when the surface looks inviting and the day feels windless. Long gaps between help, no routine lifeguard coverage, and currents that pull hard near changing sandbars make the ocean a place to admire, while freshwater lakes, creek swims, and calmer, signed spots carry the safer swim story.

Cape Tribulation, Queensland, Australia

Cape Tribulation looks like a dream border between rainforest and reef, but northern Queensland water rules are different by design. Parks guidance warns that crocodiles may live in local waters even when no sign is visible, and safety resources highlight marine stingers as a seasonal hazard, especially in warmer months. That mix turns the shoreline into a place for long walks, creek viewpoints, and sunrise photos, while swimming becomes something planned only in clearly designated areas, after checking local conditions, and with advice taken seriously. Queensland DECSI

Playa Grande, Guanacaste, Costa Rica

Playa Grande is a serious surf beach, and its beauty hides the simplest problem: rip currents that pull like a conveyor belt. Safety advocates in Costa Rica have noted uneven lifeguard coverage, which matters most on wide, open stretches where channels shift after storms and river mouths deepen the flow. When swell rises, exits get difficult fast, so locals watch for gaps in breaking waves, avoid the river-mouth pull, and choose calmer, patrolled beaches when the ocean turns loud, because fatigue arrives quickly in moving water.

Muriwai Beach, New Zealand

Muriwai sits close to Auckland, yet it behaves like a high-energy coast with strong surf, shifting sand, and pronounced rip channels. Research at the beach found that most people struggle to identify rips in real conditions, which helps explain why confident waders can be wrong at the worst moment and step into the flow without noticing. Surf Life Saving guidance keeps it simple: swim between flags when patrols are present, avoid unpatrolled water, and respect side currents that form near darker gaps where waves stop breaking and water funnels back out. nhess.copernicus.org+1

Skeleton Coast, Namibia

The Skeleton Coast is cinematic, where dunes meet cold Atlantic water and fog can erase distance cues in minutes. The coastline earned its reputation from sandbars and treacherous currents that historically wrecked ships, and the ocean still does not welcome casual swimming on most stretches, especially away from staffed lodges. The Benguela Current keeps water cold, surf can be heavy, and remote access stretches response times, so the safest relationship here is admiration from dry sand and warm layers, letting the sea keep its edge.