We may earn money or products from the companies mentioned in this post. This means if you click on the link and purchase the item, I will receive a small commission at no extra cost to you ... you're just helping re-supply our family's travel fund.

Some road trips chase scenery. Others chase the places where ideas changed the course of history. Across mesas, river plains, and a handful of purpose-built towns, the Manhattan Project left traces that still feel strangely intimate: a modest museum gallery, a quiet lodge, a sculpture on a campus lawn. These stops balance awe with context, pairing big consequences with human-scale rooms and streets. The route stitches together New Mexico, Tennessee, Washington, and beyond, where secrecy once ruled and stories now do.

Los Alamos Visitor Center

Downtown Los Alamos offers the rare feeling of walking into a story that once had no street map, only code names and checkpoints. At the National Park Service visitor center, rangers frame how Project Y operated inside an ordinary-looking town, with a short film, exhibits, and on-the-ground context for what sits on the next block and what remains behind laboratory fences, and why the mesa geography mattered. Passport stamps, ranger talks, and a quick run-through of access rules, closures, and partner museums help turn the drive up the hill into a coherent narrative, not just a detour taken on curiosity alone before any exhibit door opens now.

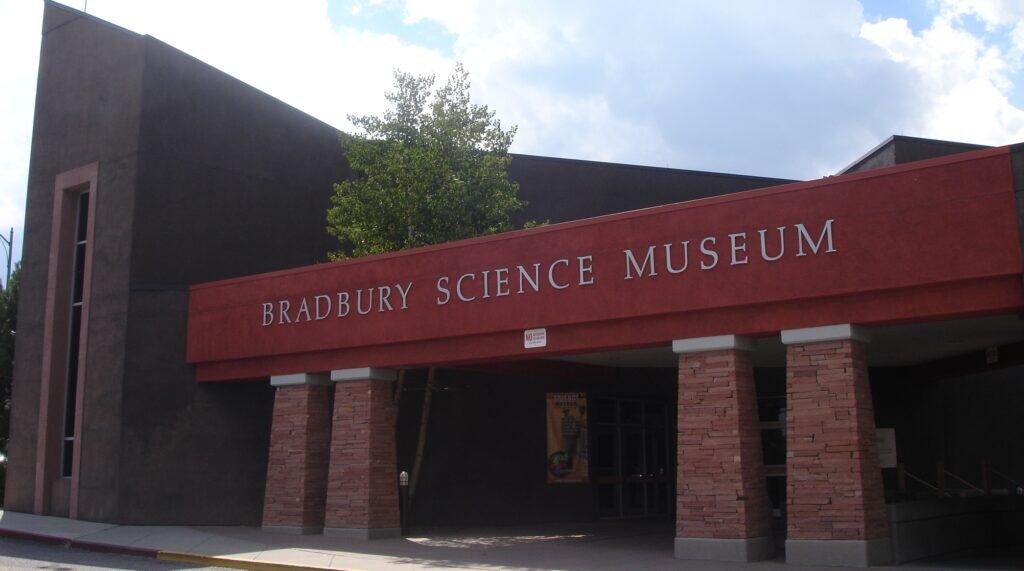

Bradbury Science Museum

The Bradbury Science Museum translates an era of locked doors into a set of hands-on rooms where the stakes stay clear, even for travelers with only an hour. Exhibits move through three broad galleries, pairing Manhattan Project history with the continuing work of the laboratory, and using models, video loops, and tactile displays to keep the science grounded and the timeline brutally fast. Free admission and a downtown location make it an easy anchor between mesa viewpoints and Bathtub Row, and the experience often leaves visitors with a quieter kind of awe: informed, unsettled, and human long after the drive back down the hill quietly, too.

Bathtub Row and Los Alamos History Museum

Bathtub Row feels almost disarmingly domestic for a place tied to the birth of the nuclear age. A short walk links stone cottages and porch lines to names that tend to live only in textbooks, with signs pointing toward the Hans Bethe House and the Oppenheimer House, and the old Power House at the end of the lane; nearby, the Los Alamos History Museum sets the Ranch School era beside the Manhattan Project years. Even when interiors are closed, the street still does the work, shrinking consequence down to chimneys, sidewalks, and the ordinary quiet of a neighborhood where secrets rode in the backseat of school runs and the ordinary kept moving.

Trinity Site Open House at White Sands Missile Range

Trinity is where the abstract became irreversible, and the landscape still holds that tension in the wide silence. Public access is limited to occasional open house days set by White Sands Missile Range, and schedules can change or be canceled, so the trip carries a strange mix of planning and patience. The drive through open desert, the basalt obelisk at ground zero, and the distant mountains make the history feel less like a chapter and more like a place with consequences that never fully left.

Oak Ridge Visitor Center at the Children’s Museum

Oak Ridge was built at speed, and the modern town still carries that purposeful geometry in its roads and ridgelines. The Manhattan Project visitor center, located within the Children’s Museum of Oak Ridge, gives the clearest on-ramp into the Secret City’s mix of ordinary neighborhoods and extraordinary industry, with exhibits, a short film, and staff who answer the practical questions that guide the day. Passport stamps, local maps, and a run-through of nearby museums and behind-the-fence bus tours help the Tennessee portion begin with clarity, not rumor or myth especially for visitors surprised by how much still sits behind gates, quietly.

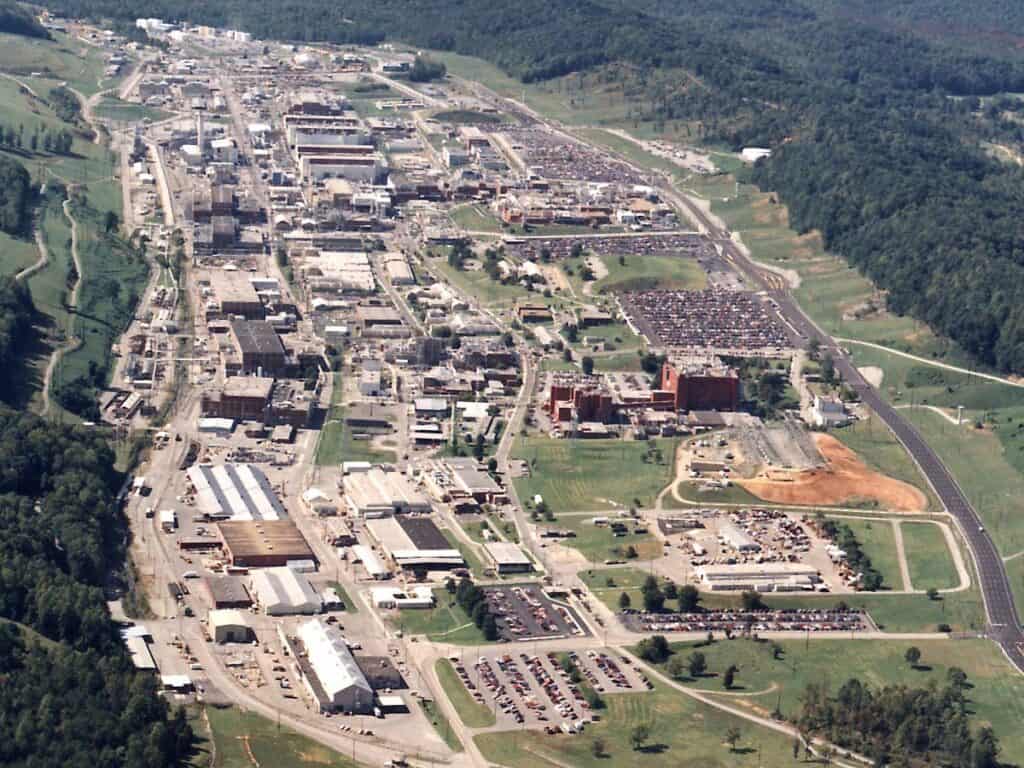

American Museum of Science and Energy

The American Museum of Science and Energy keeps Oak Ridge’s story legible, turning an alphabet of wartime code names into exhibits that connect people, machines, and consequences in plain language. Hands-on displays and artifacts trace how a valley became an industrial experiment almost overnight, then follow the thread into postwar research, energy, and national security, so the Manhattan Project years read as a beginning rather than a sealed chapter. Because the museum also serves as the hub for certain Department of Energy public bus tours, it doubles as both a museum day and a launch point for deeper, guided access with ID check required.

K-25 History Center

The K-25 story is one of scale: a uranium-enrichment effort so vast it reshaped an entire valley and left a ghost outline in maps, and memories. At the K-25 History Center, exhibits and films explain how gaseous diffusion worked, why the site mattered for producing material used in the Hiroshima bomb, and what it meant to build a secret industrial city almost from scratch, staffed by thousands whose names rarely appear in headlines. Set in Oak Ridge’s modern streets, the center’s calm pace becomes a counterweight to the subject’s enormity, letting the daily routines and hard tradeoffs come back into focus and weight lingers in the room today.

New Hope Center at Y-12

At Y-12, the Manhattan Project’s urgency took the shape of production lines and relentless shifts, turning physics into output under intense pressure. Inside the New Hope Center, a public interpretive space at the Y-12 National Security Complex, exhibits trace that work from the original plant mission to later decades, including the often-overlooked story of the Calutron Girls whose hands kept the enrichment process running. It is a compact stop, but it delivers a lasting impression: world-changing results came from repetitive tasks, careful attention, and thousands of people doing hard work without the luxury of context in plain sight again.

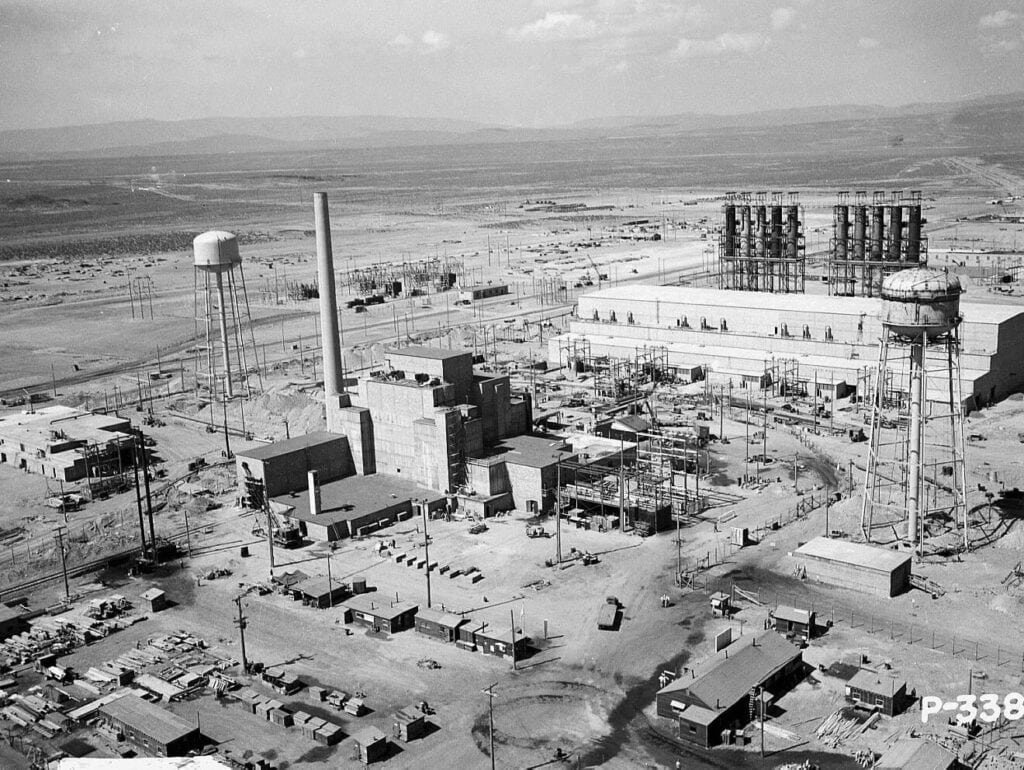

Hanford Visitor Center in Richland

Hanford’s Manhattan Project footprint is hard to grasp on a map, because it was designed to be enormous, remote, and controlled. The Hanford Visitor Center in Richland translates that scale into story, tracing how reactors along the Columbia River produced plutonium that fed the Trinity test and the Nagasaki bomb. Ranger programs, exhibits, and local wayfinding connect the secure site to the towns that sprang up around it, and the mood is equal parts engineering feat and lingering reckoning.

B Reactor Guided Tour at Hanford

B Reactor is often described as the place where the plutonium production era truly began, and standing near its control-room relics makes that claim feel tangible. Access typically requires a Department of Energy–run guided tour, and availability can shift with site operations and construction, so it rewards flexibility and a willingness to plan around narrow windows. When it is open, the experience is blunt and unforgettable: industrial spaces built for speed, then preserved as a reminder of what that speed delivered.