We may earn money or products from the companies mentioned in this post. This means if you click on the link and purchase the item, I will receive a small commission at no extra cost to you ... you're just helping re-supply our family's travel fund.

Travel has always carried a quiet promise that beloved places will still be there when the timing finally works out. Yet history does not keep that promise. Fragile caves are sealed to survive their own fame, sacred landscapes are locked down to protect vulnerable communities, and icons that once defined postcards now exist only in records, replicas, or memory. Across continents and centuries, each disappearance reveals the same tension between wonder and damage. What remains is not absence alone, but a sharper understanding of what preservation, loss, and time really cost.

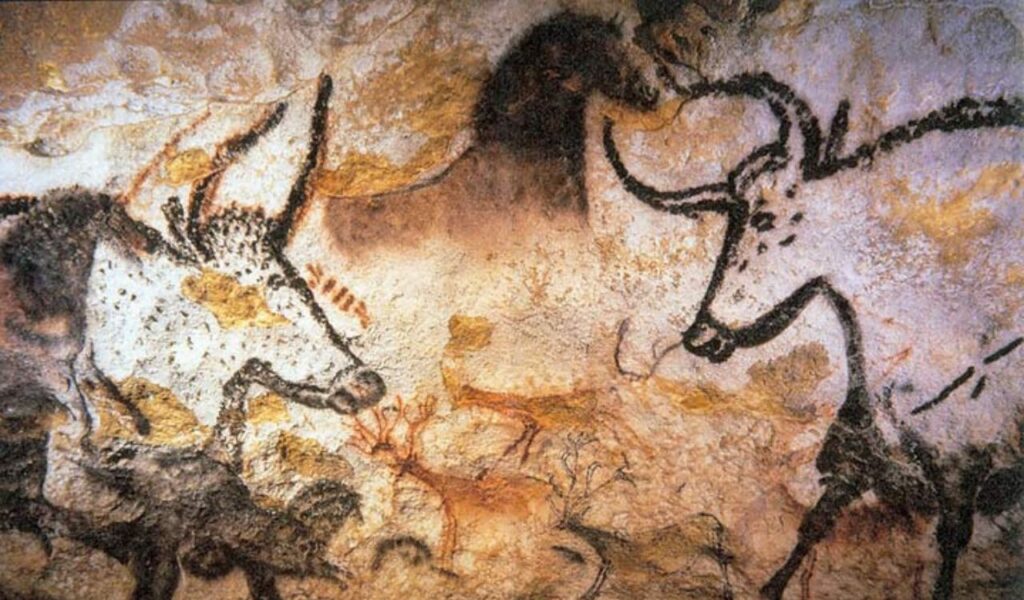

Lascaux Cave, France

Lascaux’s Paleolithic paintings became globally famous after World War II, and heavy visitor traffic quickly altered the cave’s humidity, carbon dioxide levels, and microbial balance. By 1963, authorities closed the original cave to the public, and replicas later became the primary way people experience its art. The decision changed conservation policy worldwide, because it proved that even careful tourism can overwhelm prehistoric environments. Lascaux still exists, but the real chambers now belong mostly to science, monitoring, and slow preservation rather than ordinary travel.

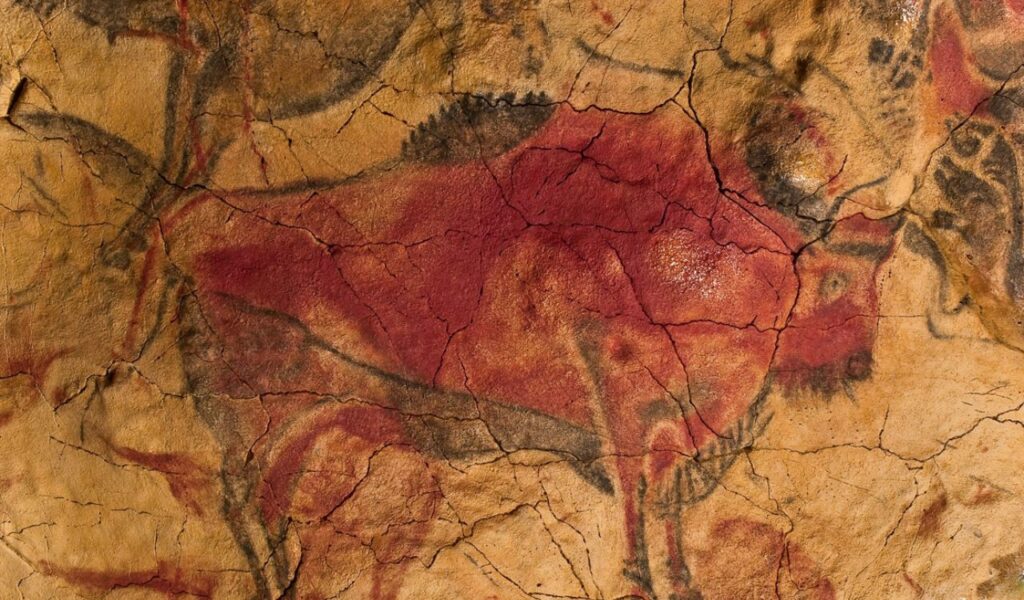

Altamira Cave, Spain

Altamira helped rewrite the history of prehistoric art, but popularity also threatened the paintings. Spain’s cultural authorities now run access under an ultra-limited protocol, allowing only a tiny number of people each week under controlled conditions. For nearly everyone, the real cave is functionally off-limits, and the museum experience carries the public burden of interpretation. The restriction reflects a hard lesson repeated at decorated caves across Europe: irreplaceable wall art can be protected only when mass visitation ends. Altamira remains famous, but not broadly enterable.

North Sentinel Island, India

North Sentinel is known worldwide because of the Sentinelese, one of the planet’s most isolated Indigenous communities. Travel there is prohibited, and the restriction is tied to safety, sovereignty, and disease risk. Britannica notes that attempts to approach have ended violently, underscoring why legal barriers exist and why outsiders are kept away. In modern tourism culture, where almost every coastline seems mapped and reviewed, North Sentinel stands as a hard boundary. Some places are protected by distance, and some by law that recognizes contact itself as harm.

Ilha da Queimada Grande, Brazil

Brazil’s Snake Island is famous for dense populations of venomous pit vipers, especially the golden lancehead. Public entry is not normal tourism; sanctioned access is tightly controlled, and reference sources note strict conditions around approved visits. The island’s reputation can drift into sensational storytelling, but the practical reality is simpler: it is treated as a protected and dangerous site, not a casual stop. Its mystique keeps growing online, while actual foot traffic remains minimal by design. Fame made it legendary, yet policy keeps it largely out of reach.

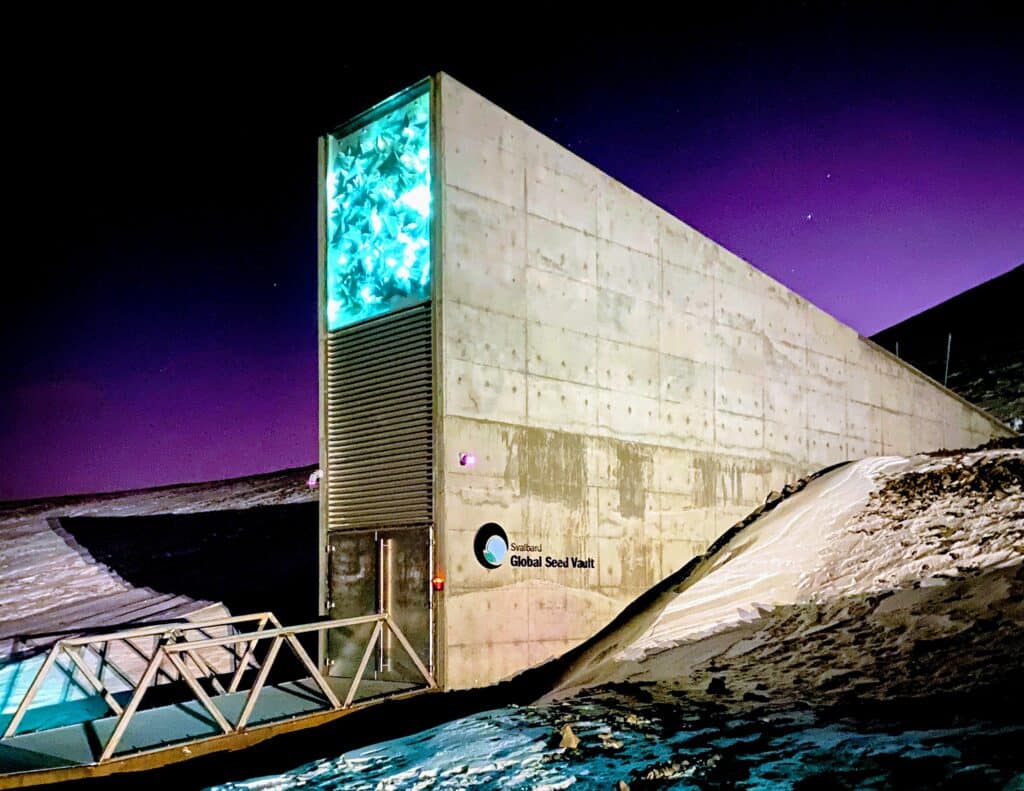

Svalbard Global Seed Vault, Norway

The Seed Vault near Longyearbyen stores backup crop diversity for global food security, but it is not a visitor attraction in the ordinary sense. Official local guidance states clearly that the facility is not open to visitors, though guided routes may pass near the entrance. That distinction matters: people can see the exterior context, but not enter the core storage function. In cultural terms, the vault became famous as a symbol of planetary resilience, while remaining physically closed to public access. Its mission is long-term security, not tourism throughput.

The Crystal Palace, London

The Crystal Palace once embodied industrial ambition, mass spectacle, and Victorian confidence in engineering. Then fire destroyed it in 1936, ending any possibility of visiting the original structure. Britannica records the loss as a decisive break between an era of monumental exhibition culture and the memory that followed. What remains now is a place-name, archival imagery, and historical influence rather than a surviving building. The site still carries emotional weight because it represents a kind of modernity that vanished in a single event, faster than anyone expected.

New York’s Original Penn Station, United States

The first Penn Station was demolished in 1963, and its destruction became one of the most cited turning points in American preservation history. Britannica’s record captures the basic fact, but the cultural aftershock was larger: a city recognized too late that grandeur can disappear through policy, not disaster. The current station serves the same transportation function, yet the original civic architecture is gone for good. It remains a textbook case of a famous place that cannot be revisited except through photographs, oral memory, and debates about what cities should protect.

Kowloon Walled City, Hong Kong

Kowloon Walled City became a global symbol of density, improvisation, and urban contradiction. The Hong Kong government announced demolition in 1987, and the area was ultimately replaced by a park, with only selected heritage elements retained. Its removal transformed an intensely lived space into a curated memory landscape. People can still visit the park and surviving historical components, but not the original walled city’s built fabric or social maze. The place remains famous precisely because it no longer exists in its former form, only in documentation and collective imagination.

Azure Window, Malta

Malta’s Azure Window was one of the Mediterranean’s most photographed sea arches, then collapsed during storms in March 2017. Contemporary reporting documented both the geological loss and the emotional public response that followed almost immediately. After the collapse, travelers could still reach the coastal area, but the landmark itself no longer existed above water. That distinction turned many itineraries into acts of remembrance rather than sightseeing. The site still attracts attention, yet the object of attention has shifted from a standing arch to the story of how quickly natural icons can vanish.

Buddhas of Bamiyan, Afghanistan

The giant Bamiyan Buddhas, carved into cliff niches, were destroyed in March 2001, an event UNESCO identifies as a defining cultural tragedy. Their niches and surrounding archaeological landscape remain historically important, but the monumental standing figures are gone. That makes Bamiyan a deeply altered destination: significant, visitable in parts, and still central to heritage discourse, yet permanently changed by targeted destruction. The place is now discussed as much through absence as through surviving material. Few losses illustrate more clearly how cultural memory can outlive the physical forms that once carried it.