We may earn money or products from the companies mentioned in this post. This means if you click on the link and purchase the item, I will receive a small commission at no extra cost to you ... you're just helping re-supply our family's travel fund.

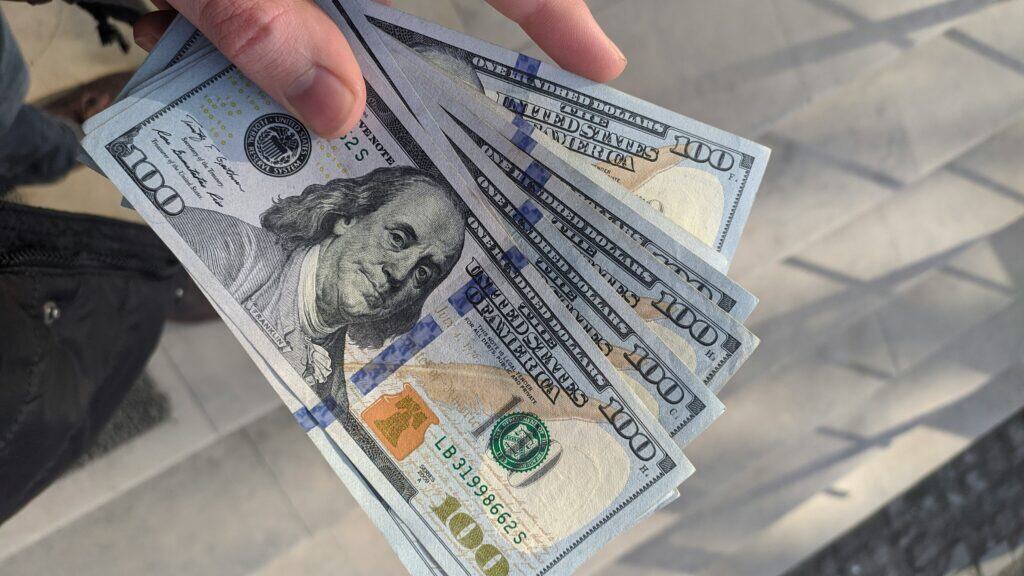

A trip can feel effortless until a checkout terminal blinks an error and the backup plan turns out to be wishful thinking. Sanctions do not just reshape headlines; they reach into everyday logistics, especially payments. In a handful of countries, U.S.-issued cards can fail consistently because card networks, banks, and merchants avoid transactions that might violate U.S. rules or trigger compliance alarms. The result is a quieter kind of friction: cash hunts, prepaid workarounds, and plans that have to be paid in advance. Knowing where plastic goes silent helps travel stay calm, even when politics do not.

Cuba

In Cuba, U.S. credit and debit cards are widely unusable on the ground, so everyday purchases lean hard on cash. That reality forces travelers into a rhythm of currency exchanges, careful budgeting, and a habit of carrying smaller bills for taxis, cafés, and tips. Hotels and tour desks often expect payment up front, and an ATM plan can fall apart quickly. Many visitors arrive with U.S. dollars or euros, then swap into pesos at authorized exchange points, keeping receipts and amounts organized. Policies can shift, but card access rarely does, so cash planning shadows the day. Even nice shops may watch a terminal time out.

Iran

In Iran, international card networks sit outside daily life, and Visa or Mastercard transactions typically do not function because of sanctions-linked isolation. Payment becomes tactile: stacks of rial for markets, prearranged hotel deposits, and mental math as prices shift between neighborhoods. ATMs generally do not accept foreign cards, so a lost cash envelope can become a problem. Some visitors rely on locally issued prepaid solutions arranged through travel services, but those still run inside Iran’s domestic system. For most trips, cash and a spending plan carry the day, even in major cities.

North Korea

North Korea is a near-total cash environment for visitors, with U.S. government guidance noting that credit cards and checks cannot be used. Most travel is arranged through tightly controlled itineraries, so payments happen in advance and changes on the fly are limited. ATMs are not a dependable fallback, and banking facilities for foreigners are scarce, pushing tour groups toward euros, Chinese yuan, or U.S. dollars. Small denominations matter, because making change is not guaranteed either. The practical effect is simple: the trip runs on paper currency and prebooked services, not swipes and tap-to-pay for most visitors.

Syria

In Syria, card payments are broadly unavailable in practice, and U.S. travel guidance notes that credit card payment is not available. Even in larger cities, the basics tend to run on cash: fuel, groceries, and transport settled face-to-face, often with prices that reflect scarcity. Sanctions, damaged financial infrastructure, and limited international banking links make foreign card processing a nonstarter. Hotels and drivers commonly want payment up front, and medical providers typically require cash as well. It is a country where payment plans become part of the itinerary. Even shops may lack functioning terminals.

Russia

In Russia, U.S.-issued Visa and Mastercard cards generally stopped working after the networks suspended operations, severing routine processing for many travelers. That change reshaped small moments: restaurant bills, rail tickets, and hotel incidentals that once felt automatic now require local alternatives. Domestic cards can run through Russia’s internal systems, but foreign-issued cards often fail at terminals and ATMs. As sanctions broadened and banks grew cautious, even online bookings and app payments became unpredictable, pushing expenses into cash, transfers, or paid-ahead arrangements.

Belarus

Belarus sits under U.S. sanctions that target parts of the state and financial system, and many U.S. issuers treat transactions there as high-risk. Declines are common when a merchant banks with an institution caught in sanctions screening, or when cross-border settlement routes look uncertain. Some banks block the country outright on prohibited-use lists, so authorizations can fail without warning. The practical rhythm becomes cash and prepayment, with extra time for exchange points and safe storage for larger amounts. Even in Minsk, modern terminals can mask a blocked settlement path that never clears.

Myanmar

Myanmar’s payments landscape is cash-forward, and sanctions risk can make U.S.-issued card transactions unreliable even where terminals exist. When an acquiring bank or counterparty raises compliance flags, U.S. issuers may decline the charge rather than guess. Some U.S. banks place Myanmar on restricted-use lists, turning cash into the default for restaurants, domestic flights, and guides. In hotels, card acceptance can look modern, then fail at authorization during outages or weak network links. Paid-ahead bookings and paper currency usually do the real work, especially outside Yangon and Mandalay.

Sudan

Sudan has faced layers of sanctions and financial restrictions over time, and card processing can stall when banks avoid U.S.-linked settlement. Even where merchants would like to accept cards, the behind-the-scenes connections to international networks can be limited or shut off. Some U.S. institutions list Sudan among countries where card use is prohibited, which means a U.S.-issued swipe may never reach an approval screen. For those who travel, money management becomes old-school: cash exchanged when possible, small bills set aside for daily costs, and contingency funds kept separate for calm.

Venezuela

Venezuela’s sanctions landscape is more targeted than a full embargo, but it still warps payment reliability when banks and merchants fear screening trouble. A charge can be declined because an intermediary will not touch the settlement path, or because an issuer blocks the country to reduce compliance exposure. Day-to-day spending can involve fast-changing prices and multiple currencies, which makes cash planning feel like a second itinerary. Many visitors treat cards as a hopeful extra, and keep enough cash for transport, meals, and emergency lodging when terminals fail or power cuts interrupt service.

Afghanistan

Afghanistan is not under a blanket U.S. sanctions embargo, but targeted sanctions and financial de-risking still make U.S.-issued card use fragile in practice. U.S. guidance notes that funds can move so long as a transaction does not involve blocked individuals or entities, yet many institutions prefer broad blocks. That caution, paired with limited card infrastructure, means a card may be declined even at hotels or airline offices. Cash, paid-ahead bookings, and locally arranged transfers often do the real work, while cards serve mostly as identification. Outcomes can change by bank, route, and week.

Leave a Reply